Burundi’s regime has decided to proceed with municipal, legislative, and presidential elections tomorrow, despite the coronavirus pandemic. The situation is tense, as concerns about post-election violence and the unchecked spread of the virus increase.

While these elections should mark the end of President Pierre Nkurunziza’s 15 years of authoritarian rule over the country, after the election he will assume the title of the “supreme guide to patriotism” in which he will have an advisory role on issues relevant to national security and national unity.

Introduction

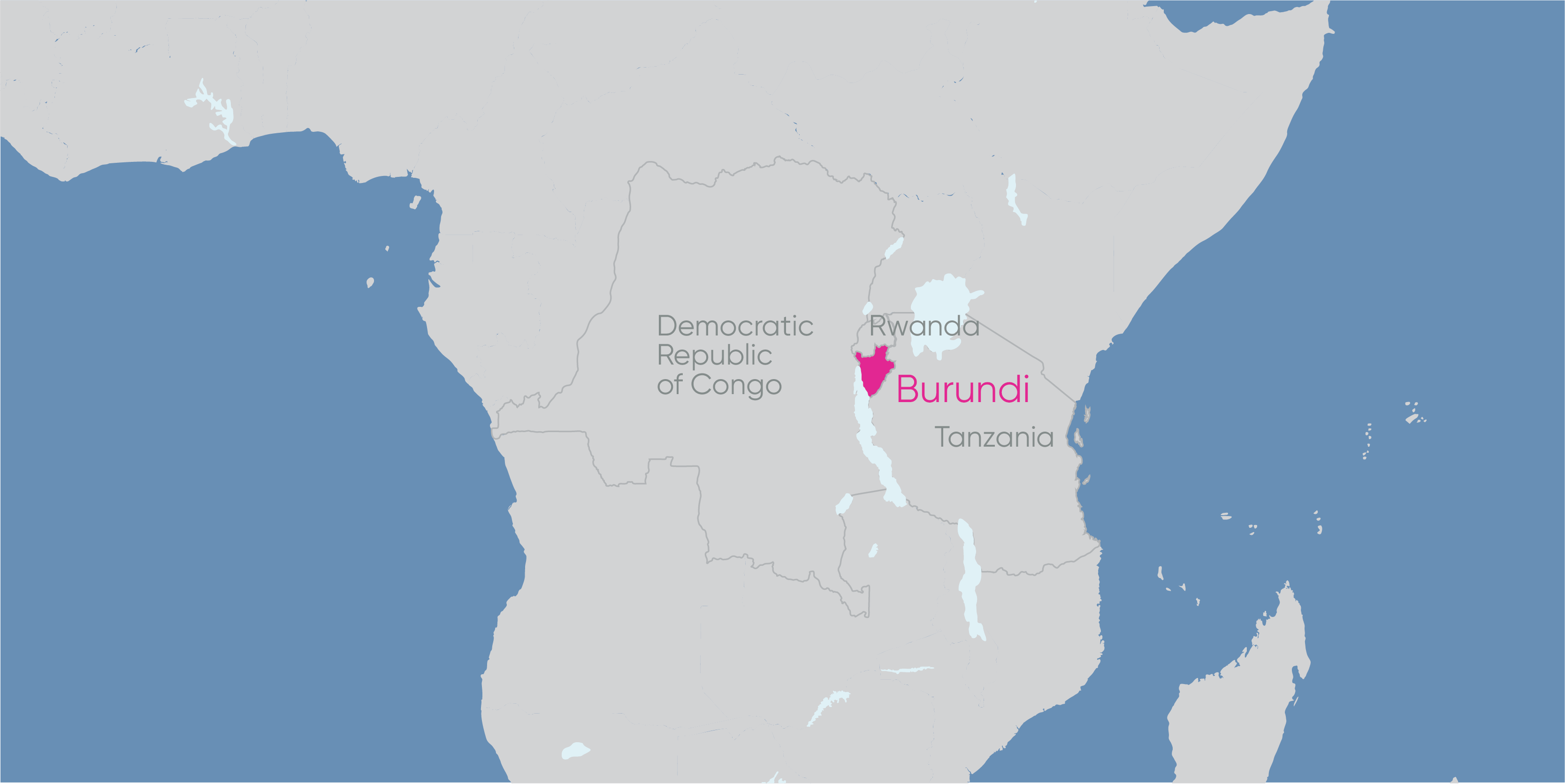

Burundi is a country in East Africa that borders the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, and Tanzania. Since its independence in 1962, Burundi has been mired in an unending cycle of ethnic violence between the majority Tutsi and minority Hutu ethnic communities. The country is ranked 185 out of 189 in the most recent Human Development Index, and its population of around 12 million people is among the poorest in the world.

The global coronavirus pandemic has exacerbated Burundi’s already-compromised conditions, as it was reeling from a 2019 malaria epidemic that killed 1,800 people, along with two cholera outbreaks that year, and a measles outbreak that emerged in November. To date, 27 cases of the novel coronavirus have been reported as confirmed in Burundi, with one death. However, testing remains scarce: only 527 tests have been carried out, and unlike its African counterparts, the Burundian regime has not taken any lockdown measures in response to the virus.

While the coronavirus has impacted countries with democratic and authoritarian regimes alike, an absence of checks and balances, in combination with a lack of transparency and access to information in authoritarian regimes, has allowed them to use the pandemic as an excuse to tighten their grip on power through a wide range of measures, including the abuse of state of emergency laws, incitement and defamation laws, and engaging in disinformation campaigns and censorship. Burundi’s regime is following the same pattern while jeopardizing the health and safety of its people in the process of holding the elections tomorrow.

Political Regime Background

Burundi is ruled by a fully authoritarian regime that is notorious for its grave and widespread human rights abuses, including extrajudicial executions, disappearances, arbitrary arrests, beatings, and intimidation. The regime operates with no accountability, due to the lack of independence of the judiciary.

President Pierre Nkurunziza, a former rebel leader, came to power in 2005 at the end of a 12-year ethnically-charged civil war. Despite the constitutional limit of two terms, in April 2015, Nkurunziza maintained that he was eligible to run for a third term. Judges of Burundi’s constitutional court were pressured into endorsing the move as constitutionally permissible.

In July 2015, Nkurunziza predictably won his third term in office with 69.41% of the votes in elections marred by violence and an opposition boycott. His candidacy in that year’s election sparked protests and an attempted military coup on May 13, 2015 that was quickly put down by pro-Nkurunziza forces, leaving more than 1,000 people dead and more than 300,000 displaced in neighboring countries.

A 2018 referendum strengthened the presidential post, extending its term from five to seven years, and eliminated constitutional power-sharing mechanisms designed to maintain ethnic and political diversity in the executive branch of government.

2020 Electoral Playing Field

The outcome of the 2018 referendum prompted many to expect Nkurunziza to stand for a fourth term in the 2020 presidential elections, but in January, the ruling National Council for the Defense of Democracy–Forces for the Defense of Democracy (CNDD-FDD) announced Evariste Ndayishimiye, the party’s secretary-general, as its candidate.

In the upcoming elections, Ndayishimiye’s biggest rival will be Agathon Rwasa, former Hutu leader and candidate of the National Congress for Freedom (CNL) party; he was the leading opposition candidate in the 2015 and 2010 elections, although the opposition boycotted both of them. In addition, more than 140 members of Rwasa’s party have been arrested since campaigning began on April 27.

Other prominent candidates include Valentin Kavakure from the FPN-Imboneza party, Anicet Niyonkuru from the Council of the Patriots (CDP), Jacques Bigirimana for the FNL, and Domitien Ndayizeye, transitional president between 2003 and 2005, who now heads the Kira-Burundi coalition. These four candidates were initially rejected by the Burundian National Independent Electoral Commission (CENI) for not meeting legal requirements but were later restored by the constitutional court following an appeal.

As in other countries ruled by fully authoritarian regimes, elections in Burundi, however, are not a viable route to power for the opposition, and there is no uncertainty about their outcome.

The electoral playing field remains heavily skewed in favor of the ruling party — Ndayishimiye, the hand-picked prospective successor was even presented on election posters as the “heir” of President Nkurunziza.

2020 Elections, COVID-19, and Human Rights Implications

Ahead of the elections, the government has methodically moved to suppress all barriers to its authority, and assaults on human rights continue largely with impunity. The political and security environment in Burundi does not guarantee free and fair elections, and elections in the country are a mechanism to perpetuate repression. Activists have been forced to flee the country in the face of persistent intimidation or have been imprisoned, tortured, or murdered.

CNDD-FDD’s militia, the Imbonerakure, has engaged in a campaign of intimidation and violence against the opposition, who have been placed under surveillance, faced threats, and even been killed. For instance, on February 20, a CNL party member was arrested in Bujumbura and died in detention. The following month, a CNL party leader in Migera, Méthuselah Nahishakiye, was assassinated after having been threatened by the Imbonerakure, whose members have been ordered to use whatever means necessary to influence voters in favor of the CNDD-FDD party, “even to use force or kill someone.”

Burundi operates with almost no independent media or civil society. NGOs are met with immense operating challenges, resulting in increased barriers to assistance. With most independent outlets and journalists having been forced to shut down or operate from exile, the press group Iwacu remains the only major independent news site still in the country. Iwacu operates under intense government intimidation and censorship, and four of its journalists have been imprisoned since October 2019 on trumped-up anti-regime charges for attempting to cover fighting between government forces and rebels. On April 11, journalists of independent media were blocked from attending a COVID-19 press conference held by the Ministry of Health. Only the RTNB, Rema and Mashariki TV — all close to the regime — were allowed coverage. And in early May, Burundi’s National Communication Council hosted its Media Awards, applauding the very security forces that are complicit in serious human rights abuses, including torture and extrajudicial killings. The Awards recognized “the role of the media in ‘sanitizing’ the context for the 2020 elections in Burundi” and fittingly awarded first prize in the television category to the national police communications team. Meanwhile, the winner in the print media category has been in hiding due to threats, and was unable to collect his award.

To add insult to injury, Burundi is also experiencing a humanitarian crisis that has left more than 15% of the population in need of humanitarian assistance. Citizens already facing immense economic strain as a result, were further distressed when the government began collecting “voluntary” contributions to cover costs of the 2020 elections. Contributions were deducted from government employees’ salaries, and those who refused to contribute were met with threats and violence.

Burundi’s prior crises that left an atmosphere of intimidation and terror — including its deadly civil war — are compounded by the current health crisis. Burundi has witnessed a total neglect in its response to the pandemic, blocking international aid groups’ offers of assistance and, in its most recent negligent move, Burundi moved to expel members of the country’s World Health Organization team, including the national head, labeling each a “persona non grata.” Borrowing a tactic from the dictators’ playbook to quiet investigators of rights abuses, Burundi had previously expelled other international representatives — last year, the government forced the country’s UN Human Rights office to close.

While the pandemic demands principled and informed leadership, the government has instead demonstrated an indifference to the protection of human rights. Institutions actively taking steps to combat COVID-19 have been threatened for seeking to “manipulate or disorientate public opinion.” President Nukurunziza, meanwhile, has been loath to enforce preventative and assistive measures to slow the virus’ spread. As the pandemic grew worse and worse around the world, the regime shrugged off the threat, invoking divine protection. “Do not be afraid. God loves Burundi,” declared Evariste Ndayishimiye, the ruling party candidate during a campaign rally. “If there are people who have tested positive, it is so that God may manifest his power in Burundi.”

The regime’s deliberate and dangerous decision to hold a major election during a global pandemic, is also a startling indicator of its repressive measures and callousness toward human life. As social distancing measures have become the norm worldwide, religious services, and mass gatherings for political campaign rallies are still the norm in Burundi. Nkurunziza’s recklessness was echoed in one of his senior advisor’s statements, indicating that people who were prevented from “enjoying” their everyday lives would “suffer” more from these restrictions than from the fatal coronavirus.

Lastly, and most importantly, the vast deprivation of liberties in Burundi has implications for numerous fundamental human rights under international law, most glaringly, the right to life. Burundi’s Constitution guarantees the right to life (Article 24) and states that the Government has the task of guaranteeing that all Burundians are “sheltered from…fear, discrimination, disease, and hunger” (Article 17) — all of which the regime has unmistakably violated. Burundi has similarly guaranteed the right to life under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Article 6 – ”No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his life”) and the African Charter of Human and Peoples’ Rights (Article 4 – ”Every human being shall be entitled to respect for his life”).

Conclusion

Regionally, the novel coronavirus has been exploited both to hold, and hold off on, elections. In Uganda, for example, President Yoweri Museveni stated that given the pandemic, it would be “madness” to proceed with next year’s scheduled elections, signaling his desire to ensure his hold on power beyond his then-35 years in office. However, Burundi’s regime has pressed ahead with elections at any cost. The climate of fear in the country, imbued with human rights violations and other ordeals, has contributed to heightened anxieties surrounding the upcoming elections, and the vice president even remarked, “Those who want to postpone the elections due to the coronavirus are enemies of democracy.”

For strongmen like Nkurunziza, a pandemic is prime time to hold an election. The government’s persistence in airing this electoral show, despite its health risks, has left little uncertainty as to the outcome of tomorrow’s elections, which will most certainly be neither free nor fair. Voters may well be unwilling to risk their lives at the polls.

Authorities have dissuaded international election observers from coming into the country, declaring that they would be subjected to a 14-day quarantine, and recommending local observers instead. Additionally, Burundi’s electoral commission is unsurprisingly made up primarily of CNFF-FDD members, as are the local chiefs. The commission has failed to publish voter lists, and voter cards to be distributed by local chiefs will likely go only to CNDD-FDD supporters.

Within this context, the international community must pay close attention to the developments that will unfold this week as Burundi goes through with its elections, and hold its regime accountable for targeting the opposition, censoring the media, and endangering the lives of its citizens.