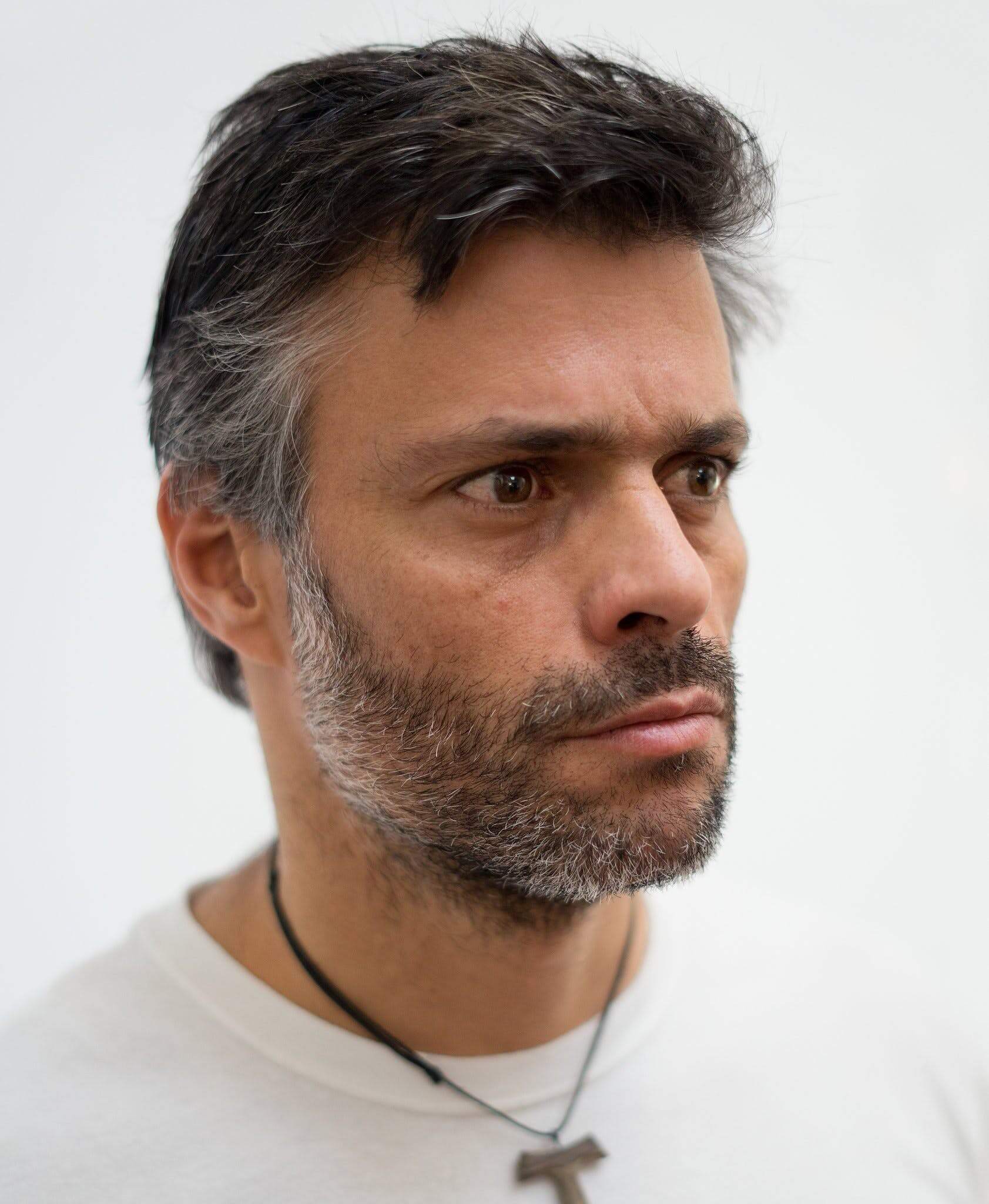

There’s a page in a book in a stack on the floor at the house of Leopoldo López that I think about sometimes. It’s a page that López revisits often; one to which he has returned so many times these past few years, scribbling new ideas in the margin and underlining words and phrases in three different colors of ink and pencil, that studying it today can give you the impression of counting the tree rings in his political life.

The book is not set out in a way to invite this kind of attention. Almost nobody is allowed to enter the López house, for one thing, being surrounded all day and night by the Venezuelan secret police; but also, for all his flaws and shortcomings, López just isn’t the sort to dress up his library for show. Pretty much every book in the house is piled up in a stack like this one — row upon row of stacked-up books rising six to eight feet from the dark wood floors, these gangly towers of dog-eared tomes, some of them teetering so precariously that when you see one of the López children run past, you might involuntarily flinch.

The particular book I have in mind is a collection of political essays and speeches. It was compiled by the Mexican politician Liébano Sáenz, with entries on the Mayan prince Nakuk Pech and the French activist Olympe de Gouges. The chapter that means the most to López begins on Page 211, under the header “Carta a los Clérigos de Alabama.” This is a mixed-up version of the title you know as “Letter From Birmingham Jail,” which was written by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1963. King was in Birmingham to lead nonviolent protests of the sort that everybody praises now, but it’s helpful to remember that in 1963, he was catching hell from every quarter. It wasn’t just the slithering goons of the F.B.I. wiretapping his home and office or the ascendant black-nationalist movement rolling its eyes at his peaceful piety, but a caucus of his own would-be allies who were happy to talk about civil rights just as long as it didn’t cause any ruckus. A handful of clergymen in Birmingham had recently issued a statement disparaging King as an outside agitator whose marches and civil disobedience were “technically peaceful” but still broke the law and were likely “to incite to hatred and violence.”

Read the full article here.