How common is the corruption of public officials in the U.S.? Ben Freeman on what America’s “authoritarian friends” from the Persian Gulf are doing in Washington, D.C.

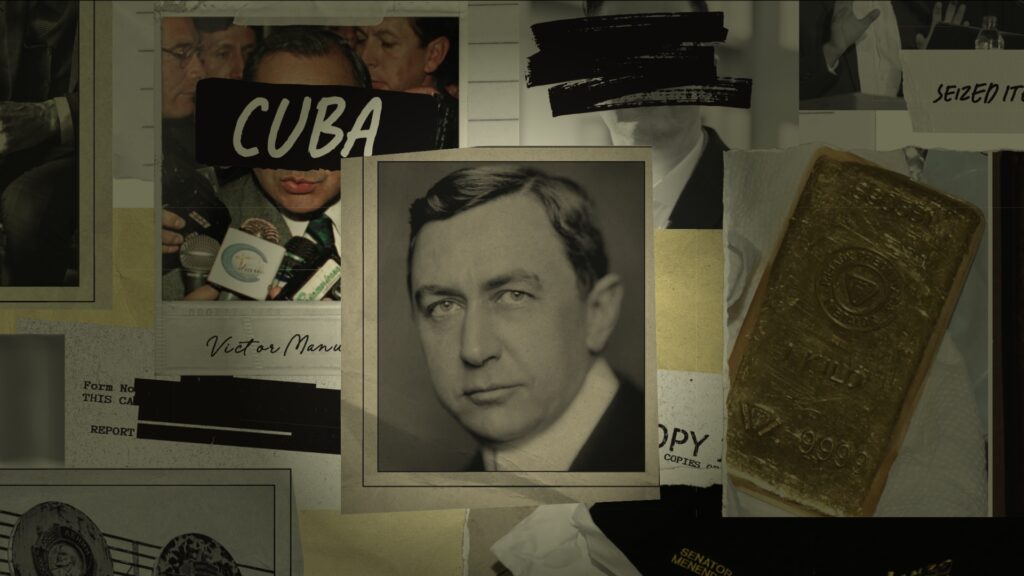

In late spring last year, a Texas grand jury indicted Henry Cuellar, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, and his wife, Imelda, on charges of accepting hundreds of thousands of dollars in bribes from the Republic of Azerbaijan and a Mexican commercial bank. A couple of months later, a New York jury convicted Bob Menendez, the former chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, also for accepting bribes— including hundreds of thousands in cash, 13 bars of gold, and a Mercedes-Benz convertible—from Egyptian officials, Qatari officials, and three New Jersey businessmen. “This wasn’t politics as usual,” said Damian Williams, an attorney for the Southern District of New York. “This was politics for profit.” A couple of months later, the U.S. Department of Justice indicted New York City’s mayor, Eric Adams, for taking more than $100,000 worth of personal bribes and millions in illegal campaign contributions from Turkish officials and companies. How much of this sort of corruption is there in America?

Ben Freeman is the director of the Democratizing Foreign Policy Program at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft and the author of The Foreign Policy Auction. Freeman says these cases are about as exceptional as they are spectacular. Of course, they’re very bad, betraying the public interest while burning public trust. But they’re unusual—not just in that the officials who get involved in them tend to be so remarkably arrogant and incompetent, but in that the criminal conspiracies themselves are so marginal to foreign-influence operations in the United States overall. Every year, foreign interests—many of them autocracies, with priorities starkly at odds with the mores of American democracy—spend hundreds of millions of dollars on these operations, through lobbying and public-relations firms, think tanks and universities, even sports franchises. And it’s all legal. But it can be difficult for most Americans to care about it, because it’s still so difficult to see …

From Altered States, a print extra from the The Signal x the Human Rights Foundation.

Gustav Jönsson: Why do you think all the high-profile cases of corruption among American politicians over the past year or so seem to involve autocratic governments?

Ben Freeman: One reason is that, you know, you take it with you: Corruption tends to be the norm in autocratic countries, so when their governments engage in corruption abroad, there’s really nothing unusual about it. It’s a fairly natural extension of how things work at home.

And then there’s the other side of it: Why do corruption cases involving American politicians tend not to involve democratic governments? Because democratic governments tend to be much less corrupt. They also tend to be allies, and so much more aligned with American goals and interests— and for that reason, much more inclined to use formal, legal channels to pursue their interests and goals, including through their embassies.

For democratic allies, resorting to underhanded tactics generally wouldn’t make sense.

Jönsson: How common are these underhanded tactics in the U.S., then?

Freeman: The headlines can be a little distracting. Foreign money buying influence is extremely and increasingly common—not least, autocratic money. But most of it isn’t underhanded and doesn’t lead to indictments, because most of it is perfectly legal.

News organizations always tend to focus on criminal cases, like Cuellar’s or Menendez’s or Adams’s. These are typically what make the headlines. Honestly, it’d be great if they were the extent of it. But they’re not, even remotely. There’s a massive, thriving, entirely non-criminal foreign-influence industry operating in the United States, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, every week.

"Foreign money buying influence is extremely and increasingly common—not least, autocratic money. But most of it isn’t underhanded and doesn’t lead to indictments, because most of it is perfectly legal."

That industry has different aspects and avenues, but the best-known is probably Washington’s K Street—the collective moniker for the D.C.-based lobbying and public-relations firms registered under the U.S. Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), which is the preeminent law in the U.S. for regulating foreign influence. The way it works is that foreign governments pay these firms to represent their interests, and to do that legally, the firms just have to register under FARA and report how much money they’re taking from whom.

There’s no legal restriction on the kinds of governments these firms can partner with, either—meaning it’s completely fine in the eyes of the law to take money from the worst tyrannies imaginable. Truly, under FARA, the only thing that could stop one of these firms from representing a foreign country or organization or person, is if any of them were subject to U.S. sanctions.

For instance, when the U.S. decided to impose sanctions on Russian “oligarch” billionaires in strategic retaliation for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, that decision cut the lobbying and PR firms off from engaging or keeping the oligarchs as clients.

But if you’re not on a sanctions list, the world’s your oyster. And so there’s really no need for shady schemes like trying to bribe people with gold bars. If you want to buy influence, there are plenty of easier, and lower-risk—because legal—ways to buy it.

Jönsson: Why would anyone still be resorting to illegal ways, then?

Freeman: Autocrats will tend to do whatever they want and think they can get away with. In the U.S., there have been strong incentives to keep that within legal bounds.

But when autocratic officials see an opportunity to do something illegal, with an American official willing to take their money under the table, the answer is, mostly, stupidity— and ego. American public figures who fall into this business generally seem to think they’re invincible, or even above the law. Like dumb teenagers.

Menendez is a perfect example. Here’s someone who’s already been investigated for corruption but managed to get out of it by the skin of his teeth—who then goes on to bag money illegally from Egyptian officials. Frankly, I’m awed by the level of hubris. The only explanation I can offer is an amalgam of stupidity and ego that’s truly extraordinary for an adult—because a guy like Menendez could easily have gotten rich through legal channels.

Jönsson: What autocracies would you say are the biggest players here—and how do you understand their goals?

Freeman: Globally, among autocratic influencers, China and Russia are the biggest players, but in terms of what they’re spending in the U.S., they’re really not up there. They buy some influence in America, of course, here and there; they’re just not the biggest spenders—or the most successful.

After Russia invaded Ukraine, the U.S. government crushed Moscow’s influence operations. Before that, they’d been in a strong position on K Street, but when the sanctions hit, Russia lost representation from the firms they were working with overnight.

"It’s completely fine in the eyes of the law to take money from the worst tyrannies imaginable. Truly, the only thing that could stop one of these firms from representing a foreign country or organization or person, is if any of them were subject to U.S. sanctions."

We’re seeing something similar with China now, too, which has become a bit of a pariah in the influence industry on account of its burgeoning great-power rivalry with the U.S. Lobbying and public-relations firms have been running away from China en masse—and for the most part, not because these firms suddenly realized they should be concerned about China’s human-rights record, but because they gradually understood that working with China was jeopardizing relationships with other clients in the Washington establishment.

These firms care about profits to the exclusion of virtually all other considerations, so if they think one of their clients is threatening their standing with five or 10 others, they’re going to drop that one client pretty fast.

The biggest players in Washington aren’t China or Russia, at any rate; the biggest players are America’s authoritarian friends in the Middle East: the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and, Saudi Arabia. You may have heard a lot about Saudi influence in the U.S. over the years since the September 11 attacks of 2001—but while the Saudi lobby is powerful, it’s not even close to the U.A.E. lobby. And that’s clear on just about every metric we’ve got. The U.A.E. is spending tens of millions a year on lobbying and public-relations firms, all registered under FARA.

On top of that, the U.A.E. has made huge investments in U.S. institutions and consumer businesses. They spend more on think tanks than the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, or any other NATO country does. They spend massively on universities, the gaming industry, Hollywood, sports—everywhere. Now, the National Basketball Association’s in-season cup is called the Emirates NBA Cup. They sponsor the U.S. Open. They’re significantly involved in virtually every major sport you can name.

The United Arab Emirates doesn’t just spend more on sway in the U.S. than other autocratic regimes; they spend more than any other government, period. They’ve developed a phenomenally expansive and sophisticated influence machine in the United States.

And by and large, the United Arab Emirates gets what it wants. In recent years, the United States has only deepened its military relationship with the U.A.E. Guess where most high-ranking retired American military officials who go to work for foreign governments end up? More than half have ended up employed by one country: the U.A.E. This country is literally buying off one former member of the U.S. military after another.

A lot of American officials consider the U.A.E. to be an important ally and working for them to be legitimate. But anyone who takes paychecks from the U.A.E.—well, you know, they’re unlikely ever to be critical of it.

Jönsson: What about Qatar?

Freeman: Qatar is on a similar trajectory, but their influence operation lags maybe five to 10 years behind the U.A.E.’s. In 2017, in the early days of the first Trump administration, a group of countries on the Gulf Cooperation Council, led largely by the U.A.E. and Saudi Arabia, initiated a blockade of Qatar. That caught Qatar unprepared on the international stage—but also, perhaps more importantly, unprepared on the American stage.

"The United Arab Emirates doesn’t just spend more on sway in the U.S. than other autocratic regimes; they spend more than any other government, period. They’ve developed a phenomenally expansive and sophisticated influence machine in the United States."

At the time, Saudi Arabia was spending piles of money on its lobbying and broader influence efforts. It wooed Donald Trump, whose son-in- law, Jared Kushner, then became close with Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. That was the beginning of the relationship between the House of Saud and the House of Trump, which in turn prepared the way for the powerful Saudi lobby you can see today.

But Qatar didn’t have any of that. So when the Saudis tried to blockade them, the Qataris recognized very quickly that they needed the kind of influence the Emiratis and the Saudis had. And they went on a blitz, hiring Trump-connected lobbyists and PR people—which they ended up expanding to include Biden-connected lobbyists and PR people. Now they’re spending tens of millions of dollars a year with FARA-registered firms on K Street.

Like the U.A.E. and Saudi Arabia, Qatar has been investing a lot in sports, as well, to improve its image broadly—“sportswashing,” as critics call it. A number of years ago, the Qataris bought the French football team Paris Saint-Germain. They’ve since hosted the 2022 FIFA Men’s World Cup. And in 2023, they bought a stake in the conglomerate that owns Washington’s professional hockey and basketball teams. They’ve made big investments in D.C. think tanks, too. So Qatar is making sustained efforts to counter the U.A.E.’s and Saudi Arabia’s influence; they’re just not all the way there yet.

Jönsson: You mention think tanks. What do these Gulf autocracies care most about, investing in them?

Freeman: Think tanks are very important to them. Qatar, for instance, is among the largest donors to the Brookings Institution—one of America’s oldest and most influential think tanks. But the fact is, most of the top foreign-policy think tanks in the U.S. take money from foreign governments—a lot of them, from autocratic governments—which, here again, is perfectly legal. No stuffed envelopes or gold bars have to change hands. The foreign government just writes a check to the think tank, which, since think tanks are non-profits, counts as a charitable contribution—so the donor even gets a tax write- off. It’s that easy.

There are certainly some activities on the shadier side, like what’s called “pay-to-play research,” where a representative of a foreign government will explicitly say, Listen, I want you to write a report on X—and I want the conclusion to be Y. The Center for New American Security (CNAS), for example, took money from the U.A.E.—and then leaked emails ended up showing that Michèle Flournoy, the head of CNAS, had been in conversations with Yousef al-Otaiba, the U.A.E.’s ambassador to the United States, after which CNAS published a report that favored the U.S. giving more weapons to the U.A.E. So that happens. But it’s rare.

What’s much less rare is foreign governments effectively buying censorship. The logic is simple: If you work at a think tank, you know who your funders are; or if somehow you don’t know who they are, and you say bad things about one of them, somebody above you in the chain of command will let you know who they are—and that what you’re saying might irritate them. Which can mean outright censorship in the moment; but even if it doesn’t, it’s likely to turn into sustained self- censorship over time.

"Most of the top foreign-policy think tanks in the U.S. take money from foreign governments—a lot of them, from autocratic governments—which, here again, is perfectly legal. No stuffed envelopes or gold bars have to change hands."

It all works almost like Darwinian selection: Authoritarian governments pay people and organizations that are friendly to them, so over time, there’ll be more of them in prominent foreign- policy positions. These governments don’t really need to change people’s opinion of them; they just need to hire enough people who already agree with them—or are predisposed to.

That’s where the U.A.E. has been so masterful. They’ve hired former military officials who come in partial to them—who see working for the U.A.E. as helping the U.S. in its war against terrorist organizations. These people might then go to work for a think tank that’s funded by the U.A.E., where they proceed unsurprisingly to say nice things about the U.A.E. A government like the Emirates’ exercises extraordinary influence this way, but the whole process is too mundane mostly ever to make headlines.

Jönsson: Why do you think there isn’t more resistance to this kind of influence in America— among either politicians or the public?

Freeman: The reason there’s not more resistance among politicians, or people in the foreign-policy community, is because of how many of them are in on it. The Washington establishment as a whole has been remarkably uncritical of the U.A.E., and one of the main reasons, in my opinion, is that the Washington establishment has been accepting a lot of their money. And almost two-thirds of the top foreign-policy think tanks in Washington take funding from foreign governments. So if those think tanks were to oppose autocratic funding, most of them would have to be willing to cut off their own organizations. But what we’re seeing is the opposite: Autocratic funding into think tanks is only growing—just as it is into lobbying and public-relations firms.

What’s more, the players on K Street are typically former members of Congress or congressional staffers—which strengthens a perverse incentive system: When a member of Congress, or a staffer working in Congress, sees people making millions outside the government, the person working in Congress starts to see a position at one of these lobbying or public-relations firms as the natural next step in their career, where they can potentially triple their salary right away. And if they’re even remotely thinking about working on K Street while they’re still in Congress, they’ll start hesitating to criticize the regimes they know are retaining those firms. They, too, will start self-censoring.

The reason there’s not more resistance among the public, I think, is that most people just don’t know much if anything at all about these governments or what they’re doing. Foreign policy is almost never a top issue for most American voters. They tend understandably to be much more concerned with pocketbook issues that affect their lives more directly. I believe that if more of them did know, they wouldn’t be pleased. But for now, that’s another world.

Unfortunately, for those who do pay attention, the media establishment routinely obscures obvious conflicts of interest that this kind of influence creates. Often, when CNN or MSNBC or Fox News has a think-tank expert come on to talk about, say, a pressing issue in the Middle East, the network won’t let their viewers know the expert they’re hearing from works at a think tank that takes millions of dollars from the U.A.E. And yet, here he is, or she is, sitting there, talking quite favorably about the U.A.E.