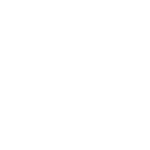

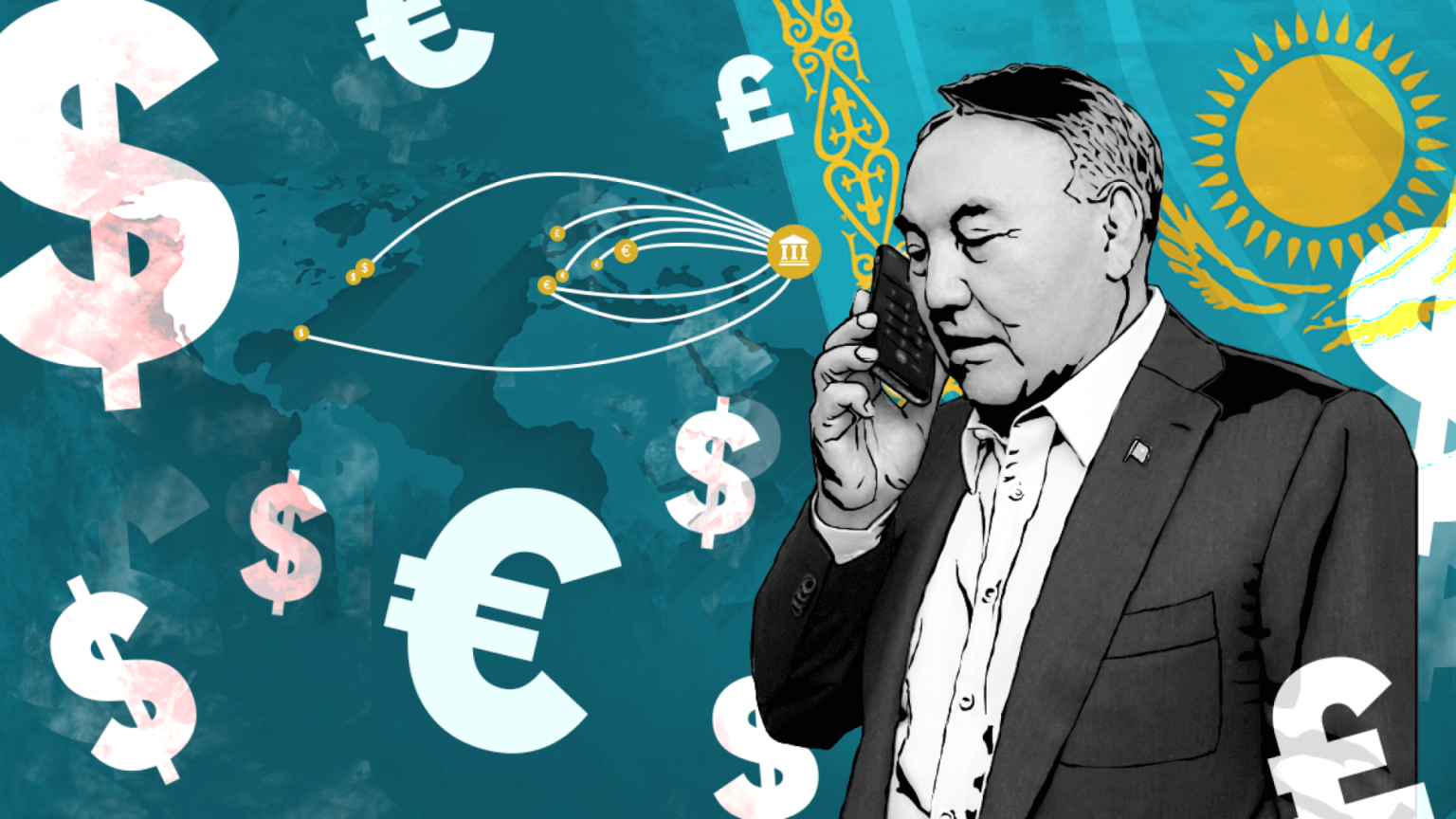

In 2005, former US President Bill Clinton traveled with mining magnate Frank Giustra to Kazakhstan and dined with its president at the time, Nursultan Nazarbayev. After the meeting, Clinton spoke at a press conference, where he lauded Nazarbayev for “opening up the social and political life” of Kazakhstan. Several days later, Giustra signed a lucrative mining contract with Kazakhstan’s state-run uranium agency, Kazatomprom, and over the next few months, the Clinton Foundation accepted over $130 million in donations from Giustra.

This story illustrates how corruption drives the regime in Kazakhstan. Since its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Kazakhstan has been ruled by kleptocrats — businessmen who exploit their political connections to the Nazarbayev family to amass vast fortunes. Nazarbayev gave up formal political power in 2019, but the corrupt system he created persists.

For example, according to an OCCRP investigation, when Nazarbayev became the ruler of Kazakhstan after independence,Vladimir Ni, his personal secretary in the 1980s, exploited the country’s transition to a market economy and acquired state-owned mining companies at bargain prices. He was then able to sell stakes in these mining companies to foreign investors, like Samsung, reaping a giant profit along the way. Using shell companies and anonymous trusts, Ni next shifted his ill-gotten gains out of Kazakhstan and into Western bank accounts, where the source of the money remains hidden. Ni died in 2010, but his protégé, Vladimir Kim, took over the venture and was Kazakhstan’s richest man in 2021.

The evidence of the stolen wealth of people like Kim and Ni is visible in the capitals of Western countries. According to London think tank Chatham House, London shelters over $530 million in property belonging to Kazakhstan’s ruling class. An investigation by journalists from Radio Free Europe found that the Nazarbayev family alone owns over $700 million in luxury real estate, from Switzerland to Florida. At every step, these kleptocrats are supported by a legion of financial advisors, lawyers, accountants, lobbyists, and consultants who ensure that no politician, journalist, regulator, or prosecutor interferes with the swift thievery of Kazakhstan’s wealth.

However, democracies like those in the UK and the US have been reluctant to investigate the sources of this wealth, at least in part because Western politicians are eager to believe the myth of the efficient dictatorship. The efficient dictatorship restricts the political freedoms and civil liberties of its citizens, but creates a welcoming environment for foreign businesses and investments to operate in association with the government and its cronies. The efficient dictatorship steals opportunities from its people, but projects an image of stability,certainty and Western-like market economy to the international community.

This myth of the efficient dictatorship has been peddled by some of the West’s most famous leaders. For decades, Western leaders, including Bill Clinton, have found it personally rewarding to embrace the myth of efficient dictatorship. Following the 2011 massacre of 17 striking oil rig workers, former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair accepted £13 million in consulting fees from Nazarbayev. The Pandora Papers revealed that former British cabinet minister Jonathan Aitken was paid £166,000 to write a flattering biography of Nazarbayev. Just last year, Hollywood director Oliver Stone made a laudatory, eight-part documentary about Nazarbayev called Qazaq: History of the Golden Man.

This corruption must stop.

Recent events have shown that the efficient dictatorship is a lie. As Kazakhstan plunges into instability, it’s time for the US and Europe to discard this false notion. The democratic community must stop helping Kazakhstan’s rulers hide their stolen money in places like London, Paris, and New York — wealth that rightfully belongs to the Kazakhstani people, but lines the pockets of Western apologists and enablers.

US President Joe Biden’s new strategy on countering corruption is a start. The plan commits to shoring up regulatory gaps, strengthening anti-money laundering legislation, and holding corrupt actors accountable. The language contained in the strategy is admirable, but it is useless without political will. In fact, the laws to punish corrupt authoritarians already exist. For example, the Magnitsky Act, which authorizes the US to sanction human rights offenders and those engaged in corruption, seize their assets, and prevent them from traveling, has been law since 2012. Similar legislation also exists in the UK and Canada. Unfortunately, more often than not, the Magnitsky Act targets the colonels and minor officials who commit crimes, rather than the oligarchs who benefit.

For years, the regime in Kazakhstan has successfully deflected attention from its brutality and corruption by paying bribes and arguing that reforms took time. The US and the European Union must act on their many promises to strengthen transparency regulations, close loopholes, and crack down on corrupt kleptocrats.

The West can start by sanctioning Nazarbayev, his family members, and other members of the country’s corrupt elite. They shouldn’t be hard to find. According to KPMG, 50 Kazakhstanis own 42% of the country’s wealth, and we know all of their names.

Repression is the first and last tool of any dictatorship. If Western democracies truly care about the long-term stability and prosperity of Kazakhstan and its neighbors, they should consider investing heavily in anti-corruption and human rights initiatives instead of hagiographies and repression.