Long before the inception of the Olympic Games in Ancient Greece, sports have been used to distract the masses, test foreign policies, thaw diplomatic tensions, and broadcast political and social messaging. In the modern era, authoritarian regimes have tapped into the popularity of sports within popular culture to manipulate domestic and global perceptions as a form of sophisticated soft power strategy.

This four-part series will delve into the history of dictators’ weaponization of sports for political indoctrination, national consensus, the distraction of the masses, global projection of soft power and prestige, and international diplomacy, analyzing its ancient roots, its popularity among dictators in the 20th century, and its modern evolution.

This piece looks at how some of the 20th century’s worst human rights abusers secured the hosting or sponsorship of some of the most prestigious international sporting events of their time, often through controversial backroom dealing, lobbying, and politically charged decisions of sports governing bodies that operate above any accountability and with little transparency.

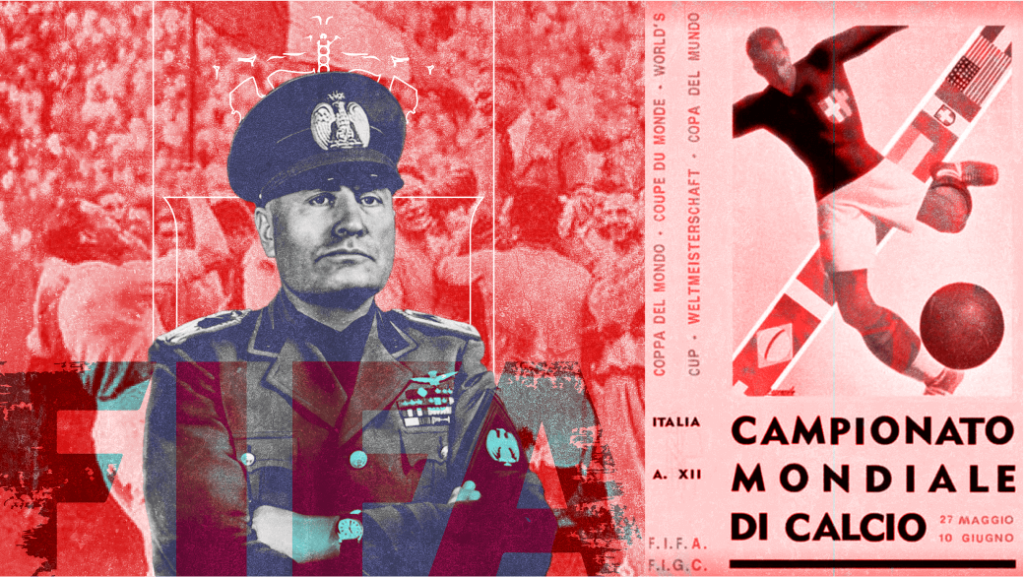

Mussolini: The “Sporting Dictator” and the 1934 FIFA World Cup

The 1920s saw the rise of fascism in Europe, starting with Benito Mussolini’s Black Shirts movement, which seized power in Italy in 1922. Mussolini pioneered the weaponization of sports for political propaganda, social control, and international soft power projection.

In this vein, the fascist regime developed centralized national policies to transform Italian society into a sports nation, linking sports to the forging of a new national identity, health, and military readiness. Popular imagery casts Mussolini as a sportsman, with a photo of the shirtless dictator gracing the January 1937 cover of the French magazine Vu with the title “Mussolini: Sporting Dictator.” With the popularity of calcio, or football, the fascist regime invested in building football stadiums to reach the common man and cultivate nationalism and fascist superiority based on the hypermasculinity of the so-called “new Italian.”

In 1932, when FIFA, world football’s governing body, awarded the second edition of the football World Cup to Italy, Mussolini saw an opportunity to grandstand and promote fascism on the world stage. “The ultimate goal of the World Cup will be to show the universe what is the true fascist ideal of the sport,” General Giorgio Vaccaro, the Mussolini-appointed head of the Italian federation, said. The regime invested 3.5 million lire in hosting the event, which it heavily politicized and stage-managed, leading FIFA President Jules Rimet to declare: “I have the impression that it was not FIFA that really organized the World Cup, but Mussolini.”

The World Cup culminated in a championship match with geopolitical stakes between fascist Italy and communist Czechoslovakia at the Stadium of the National Fascist Party (Stadio Nazionale del PNF) in Rome in the presence of Mussolini. The Italian victory was a huge success for the Italian dictator, who seized the opportunity to make a grandiose spectacle by presenting his own specially commissioned trophy to the Italian team: la Coppa del Duce, a massive, fascist-themed trophy dwarfing the official trophy.

Over the years, various reports have revealed a number of controversies, suggesting that the tournament was likely tainted by Mussolini’s interference with officiating and pressure on the Italian coach and players.

Four days after Italy’s crowning in 1934, Mussolini and German fascist dictator Adolf Hitler met in Venice for the first time. Sixteen months later, Mussolini invaded Ethiopia, and in 1937, he took Italy out of the League of Nations in protest of international sanctions for the invasion. In March 1938, Hitler invaded Austria with Mussolini’s support. None of these stopped Mussolini’s Italian national football team from securing a gold medal at the 1936 Olympics and becoming the first repeat champions at the 1938 World Cup. Each of those victories bolstered Mussolini’s dictatorial regime and helped him further promote fascism.

The 1936 Nazi Olympics

Hitler also weaponized sports as a form of nationalist propaganda, most particularly with the 1936 Olympic Games in Nazi Germany.

In 1931, the International Olympic Committee awarded the 1936 Summer Olympics to Berlin—a choice that signaled Germany’s return to the world community after its isolation in the aftermath of defeat in World War I. But in 1933, Hitler became chancellor of Germany and quickly turned the nation’s fragile democracy into a one-party dictatorship that persecuted minorities such as Jews and Roma, as well as all political opponents and dissidents. The same year, the first concentration camp opened in Dachau.

Nazi propaganda used sports imagery to cultivate the myth of “Aryan” racial superiority and physical prowess. Nazi artists idealized athletes by emphasizing well-developed muscle tone, heroic strength, and accentuated facial features deemed ostensibly Aryan. While the Nazis disdained the Olympics and what they represented, Hitler backed the hosting of the Games because they aligned with his political interests, including reducing employment, improving Berlin’s infrastructure through the construction of Olympic infrastructure, and showcasing Nazi “superiority” on the world stage.

An international boycott movement emerged, particularly in the US, but the Nazi regime found allies in American IOC members Charles Sherrill and Avery Brundage.

Brundage was a proponent of the mantra that sports and politics should be separate, urging American athletes to stay out of “the present Jew-Nazi altercation.” In reality, Sherrill and Brundage were both Nazi sympathizers who returned from visits to Germany, heaping praise on the Nazi regime. Sherill wrote a letter to US President Franklin D. Roosevelt praising Hitler’s personal character. “We have much to learn from Germany. An intelligent beneficent dictatorship is the most efficient form of government,” Brundage said in October 1936 at a pro-Nazi rally in New York’s Madison Square Garden. This did not stop Brundage from serving as IOC president from 1952 to 1972. Decades later, the Simon Wiesenthal Center claimed it had uncovered evidence that Brundage and another IOC executive, Count Henri de Baillet-Latour, had been offered bribes by the Nazi regime to promote the Berlin games in defiance of the Olympic charter and spirit.

While Brundage and Sherill prevailed over the American Olympic Committee, the public pressure from the threat of boycott did, however, lead the Committee to extract a compromise from the Nazi regime against American participation: Hitler agreed to soften the Nazi party’s hardline ban on Jewish athletes from the Games.

In the end, the Nazi regime hosted the first-ever Olympic Games to be broadcast live on television, presenting a facade of openness and unity behind the Führer. Hitler’s regime suspended its campaign against the Jewish community and even ordered newsstand owners in Berlin to remove the antisemitic Nazi smear sheet Der Stürmer from their shelves in order not to alienate international guests. Even when black American Jesse Owens won four gold medals in track and field, the German media maintained the facade of praising his exploits without any racism.

For Germans opposed to the Nazis, the Berlin Olympic Stadium was a temporary safe space and escape from the Nazi reign of terror, which allowed them to join chants cheering for Owens. “In the Olympic Stadium, we were safe. The Gestapo could not possibly arrest 100,000 spectators, probably half of them foreigners, under the eyes of the whole world,” Wolf von Eckardt wrote.

Unbeknownst to spectators and visitors; however, the Games were taking place just 35 kilometers (22 miles) south from the site where the Nazi regime had begun constructing the Sachsenhausen concentration camp just a few weeks before the olympiads. Just a couple of weeks before the Berlin Games, civil war had broken out in Spain, and Hitler’s regime was already waging war there.

Nevertheless, the Nazi regime was wildly successful. Germany mopped up the most medals by far in the Games, and to this day, the 1936 Olympic Games are remembered as one of the most successful examples of soft power projection through the medium of sports.

Imperial Japan’s 1940 Olympics That Never Were

During the Berlin games, the IOC awarded the hosting of the next olympiads to Tokyo, the capital of Imperial Japan, which had been an international pariah since leaving the League of Nations in 1933 as a result of condemnation over its invasion of Manchuria. Just like Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, the Japanese militarist regime saw hosting the Olympics as an opportunity for the projection of power and prestige on the world stage. It had secured the bid through a secret quid pro quo pact with Mussolini, who agreed to drop Rome’s bid for the 1940 games in exchange for Tokyo’s support for Rome’s bid for the 1944 Games and promise to stop selling arms to Ethiopia, which was facing an Italian military invasion and occupation. In addition, Japan offered to subsidize travel for athletes and spent $100,000 to treat the IOC and its president, Count Henri de Baillet-Latour, to an all-expenses-paid 20-day visit to Tokyo. However, Japan forfeited the hosting of the Olympics. In July 1938 — less than six months after its troops massacred up to 300,000 people in the Chinese city of Nanking in its deepening war of aggression in China. The 1940 Olympics never took place because of World War II.