Where’s all the money coming into American think tanks from? Ben Freeman on the enormous foreign-government “donations” flowing through Washington, D.C.

This article was originally published on The Signal.

Read The Signal

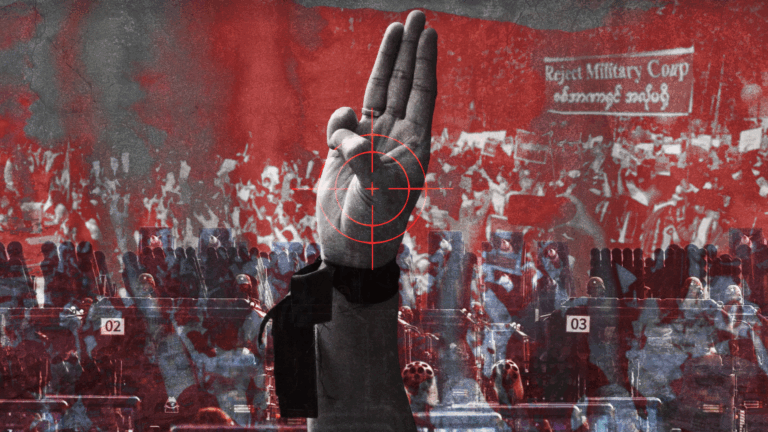

In late July, the United States Department of Defense said it would no longer participate in events with think tanks that put “America last.” Their stated intent is “to ensure the Department of Defense is not lending its name and credibility to organizations, forums and events that run counter to the values of this administration”—above all, those that promote “the evil of globalism.”

Meanwhile, however, a string of recent reports indicates a considerably less abstract issue that the U.S. administration appears unconcerned with: Foreign governments are pouring money into think tanks across Washington.

The Atlantic Council, for example—where U.S. secretaries of state often go to launch new foreign-policy initiatives—is one of the most influential. Yet the Atlantic Council has taken more than US$20 million from foreign governments over the last six years. Those giving significantly aren’t just donors; they’re “strategic partners.” And leaked emails show that one such strategic partner, Yousef Al Otaiba, currently the United Arab Emirates’ U.S. ambassador, was given the opportunity to provide comments on a draft report about American policy towards Iran.

Foreign-government funding works in subtler ways, too. For instance, following the 2018 murder of Jamal Khashoggi by Saudi intelligence operatives, the Center for American Progress (CAP) prepared a statement that called for the U.S. government to impose specific punitive consequences on Saudi Arabia. But in the published statement, CAP merely recommended that Washington “take additional steps to reassess” its relationship with Riyadh. Coincidentally or not, one of CAP’s top donors is Saudi Arabia’s own strategic partner, the Emirates.

Think tanks operate under all kinds of mission statements, most of them lofty, all of them costly to execute against. Fortunately, they can count on foreign governments to help meet those costs. But where exactly does that money come from—and what kinds of interests are behind it?

Ben Freeman is the director of the Democratizing Foreign Policy program at the Quincy Institute and the co-creator, with Nick Cleveland-Stout, of the Think Tank Funding Tracker, where you can look up which think tanks take how much money from which foreign governments.

From 2019 through 2023, Freeman says, foreign governments spent more than US$100 million on funding American think tanks. For the most part, the money comes from America’s formal allies. The United Kingdom, for instance, spends millions on American think tanks. But so do what Freeman calls America’s “autocratic friends,” principally the Emirates, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia—all signing multi-million dollar checks on the regular. As mightn’t surprise you, they aren’t doing it out of sheer generosity, either; they’re buying influence—over the American democratic process.

But what may be even more concerning, Freeman says, is that so much of this money remains untraced. With disclosure being voluntary, many think tanks simply refuse to say who their funders are or how much they’re funding. And so it’s entirely possible—in fact, very likely—that they’re systematically covering up donations from certain governments. Is it plausible, for example, that out of the more than $100 million foreign governments gave to American think tanks in recent years, only $10,000 comes from the People’s Republic of China? Freeman says we have reasons to believe it’s not …

Gustav Jönsson: A lot of people will have heard of think tanks, but what exactly do they do?

Ben Freeman: Honestly, even people working at think tanks can have a hard time saying, these days. No two are alike. Here in the U.S., they don’t even have a formal governmental designation. They have a couple of things in common, though: They’re all nonprofits, and—at least in theory—they’re intended to be something of a bridge between academia and the public-policy process; they’re here to give policy makers in the government rigorous scientific knowledge on the basis of which the government they can create public policies that benefits everybody.

The Brookings Institution is the oldest think tank in the U.S. During World War I, Robert S. Brookings, a wealthy businessman who’d worked with the U.S. government, concluded it was a major shortcoming in American public policy that it was created without the benefit of the scientific knowledge coming out of universities. He wanted to bridge that gap. And so, he set up what ultimately became the Brookings Institution, which is still a thriving think tank headquartered in Washington, D.C. Depending on who you ask, it remains arguably the most influential think tank in America, perhaps even in the world.

All of which sounds great. But there’s been a big shift over the last century from what we might call think tanks in theory to think tanks in reality. And the reality is that today, Brookings’s money no longer comes from a single benefactor with a single, relatively transparent agenda. Neither is it unique in this sense. Today, there are almost 2,000 think tanks in the U.S. and more than 4,000 around the world; all of them have to compete for funding.; and that competition can influence their work. Money, it won’t surprise you, matters immensely.

And it turns out that American think tanks increasingly get their money from special interests. Foreign governments, in particular, have started funding think tanks more and more in the past few years. But we’ve also seen other special interests, like big oil and gas companies, ramp up their funding, as have Pentagon contractors—organizations that make a lot of money selling weapons and equipment to the U.S. Department of Defense.

Jönsson: What’s driving that?

Freeman: It’s hard to say with certainty. But I have theories.

Think tanks are growing. Some of them are enormous entities. The Brookings Institution, for example, has an annual budget of almost US$100 million. It’s a gigantic organization, with scholars all over the world. It has several hundred folks on staff. And that’s not even counting their vast network of fellows. And still, Brookings is only one think tank among many. There are places like the Heritage Foundation, the American Enterprise Institute, and the Center for American Progress that have annual budgets in the tens of millions of dollars. As they’ve expanded, they’ve had to find new ways to secure funding. And foreign governments have kindly provided it.

Jönsson: Is this continuously increasing, or was it more a step change—and plateaued?

Freeman: Continuously increasing, dramatically—and likely to continue to. This year, the Trump administration has slashed U.S. government funding of think tanks. In the future, I expect we’re going to see even more think tanks looking for non-U.S. governmental sources of funding.

Jönsson: So what do these foreign governments want?

Freeman: What they want is to garner influence over American democracy. It’s the worst-kept secret in Washington, D.C. that think tanks can effectively operate like lobbying firms. If you work at a think tank, you might be testifying before Congress; you might be helping a congressional office prepare for congressional hearings; or you might, at the very least, send them your latest report. And in some cases, you’re not just providing talking points but helping them draft laws. I know because I’ve worked at think tanks for 15 years. I’ve done it all.

And every piece of that work is vital to the policy process. Now, outside forces and special interests have started to recognize that fact, too. Now, they’ve developed a more sophisticated understanding of how American politics functions. They’ve come to realize that if they make a sizable contribution to a think tank, they have some meaningful say over that think tank’s work—and that they might, for instance, have some influence over what recommendations the think tank sends to congressional offices.

Jönsson: You’ve previously said here in The Signal that most of the money going toward American lobbying firms is coming from America’s “autocratic friends,” not least the Gulf states. Do you see something similar with think tank funding?

Freeman: That’s right. It’s the usual suspects. It’s America’s “autocratic friends.” But I call them “friends” in air quotes because they don’t always share U.S. interests. In fact, they often don’t. Still, most of the countries who’re giving big money to U.S. think tanks are formal U.S. allies.

No country has spent more money on the top think tanks in the U.S. than the United Arab Emirates. By our calculations, from 2019 to 2023, the U.A.E. spent nearly $17 million on America’s top think tanks. The third biggest spender was Qatar, at over $9 million. A little further down the list, we have Saudi Arabia.

Jönsson: What is the U.A.E. getting, then?

Freeman: I think there’s a particular cause for concern when it comes to the U.A.E.

Leaked emails and investigative reporting have revealed clear incidents where the U.A.E. is getting their hands on think tank reports before they’re published.

Jönsson: Remarkable.

Freeman: Truly.

They have the opportunity to provide comments, track changes, effectively to try to play censor. They can “express their concerns” before those reports are published.

Soon enough, the people writing those reports begin to take those “concerns” on board even before they’ve finished writing them. So, even if there isn’t outright censorship, there’s going to be an element of self-censorship. If a weapons company or foreign government is providing a seven-figure check to your think tank every year, that’s going to make you hesitate before criticizing them. That’s not to say you won’t. But on the whole, you’re going to be less likely to say mean things about somebody who’s writing a big check to your employer. And if you nonetheless say too many mean things about them, believe me, your boss will tell you to cut it out.

The U.A.E. is also engaging in outright “pay to play” research, where they’re explicitly saying, We want a report on X, we’re willing to pay this or that amount of money for it, then the think tank publishes a report on just that subject.

There’s a famous example of it: Leaked emails showed that the U.A.E. embassy reached an agreement for a quarter of a million dollars for the Center for a New American Security to write a report on U.S. drone-proliferation policy. Drones are among the U.S. military’s high-end tech. And so the U.S. is very reluctant to share it with other countries. The U.A.E. wanted an analysis of that proliferation regime, to see if it should be broadened to include more countries. Lo and behold, they pay for a report on exactly this topic, and the CNAS report ultimately recommends that the U.S. expand its proliferation regime to include a number of other countries, including the UAE.

Jönsson: Such a coincidence.

Freeman: Fast forward a couple of years after that “coincidence,” lobbyists working on behalf of the U.A.E. began to push for an agreement under which the U.S. would sell this military tech to the U.A.E. That deal never went through, but it shows what’s possible. By funding think tanks, foreign governments can effectively sow the seeds of an idea within the American foreign policy elite; then they have their paid lobbyist go pitch that seemingly objective analysis to American policymakers. It’s an effective strategy. Lobbyists can’t expect to get their way if they just show up to a congressional office, saying Hey, support this-or-that policy because I say so. But they might very well succeed if they have a seemingly credible think-tank report, written by Dr. So-and-So, saying that it’s a good idea because it strengthens U.S. national security.

Jönsson: How much of this kind of funding remains untraced?

Freeman: Tracking it is very hard. There’s no central repository of think tank funding in America. In fact, there’s no requirement for funders to disclose their funders at all—those that do, are doing so voluntarily. Some will disclose it in their annual reports. Some will disclose it on tax filings. Others will disclose it on a random page, half-hidden on their website. Many think tanks keep it hidden entirely.

Jönsson: So there might be systematic underreporting, especially of money coming from certain governments?

Freeman: To use the parlance of the former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, there’s a “known unknown” here. We know it’s happening, but not much more. China, for example, has something of a scarlet letter attached to it in the U.S. No one wants to be seen taking money from Beijing.

Jönsson: But they might still be taking it?

Freeman: Precisely. They may or may not take money, but they certainly do not want to be seen taking it. Possibly, they’re pocketing big checks without reporting. We’ve seen this in Foreign Agents Registration Act cases. A few years ago, the co-head of a think tank was indicted for violating FARA largely because of her connections with the People’s Republic of China.

The issue isn’t entirely exclusive to autocracies, either—Israel being an example. The New York Times has reported that the Israeli government spoke with legal experts in the U.S. about establishing and funding a nonprofit explicitly because they didn’t want to register under the U.S. Foreign Agents Registration Act.

So it’s happening, but we have no idea on what scale.

Nick Cleveland-Stout and I have tracked over $100 million in foreign government funding. That’s a big number. But it’s the floor, not the ceiling, for how much money is really in play. It’s the very minimal level of money we could track. According to our analysis, more than a third of the top 50 think tanks in America haven’t disclosed anything about their funders—nothing. And the smaller think tanks report even less.

But even those reporting their funding—they only provide partial information. Some of them just list their funders, without indicating how much they’ve given. Others will put the funders in buckets. You might get a bucket with donations between $5,000 and $100,000. Another bucket might be $100,001 to $250,000. The next might be $250,000 and up. Well, the “up” could be $500,000 or $5 million. That’s an extraordinary difference. And so, since we cite the lower end, the true U.A.E. figure could easily be double or triple that—because the U.A.E. very often falls into the top bucket of $250,000 and above or $500,000 and above. But how far above? We just don’t know.