Altered States is a print extra created in partnership between The Signal x the Human Rights Foundation.

Corruption is everywhere. Or so you might think—because narratives of corruption are everywhere.

In the United States, Democrats and Republicans talk chronically of their opponents as being defined by it—Democrats seeing corporate influence, dark money, and foreign interference; Republicans, deep-state conspiracies, voter fraud, and graft in federal agencies. When either looks into the possibility that one or another of these things might be happening, the other claims the investigation is politically motivated. Which is to say, corrupt.

Neither is this tendency entirely new. From colonial-era anti-monarchists to contemporary conspiracy theorists, time and again, Americans have understood corruption as an existential threat to their republic—sometimes perceiving elaborate plots in sparse arrays of evidence. The country’s founders established the checks and balances characteristic of their constitution partly to limit what they saw as the corrupting influence of concentrated power.

Nor is the tendency unique to the U.S. In the United Kingdom, it’s common for Labour supporters to see the Tories as enmeshed with wealthy donors, tax-avoidance schemes, and privileged access for corporate interests—and for Tories to see Labour as corrupting Britain through union influence, local-council mismanagement, and left-wing bias in public institutions. You can find similar themes from Canada to Australia and throughout the democratic world. You can trace them back to the republican city-states of the Italian Renaissance, or back from there to ancient Athens.

And there are at least grains of truth to a lot of them.

If anything’s fundamentally different today, it’s that media is now everywhere; its dominant business model is based on engagement—the time you give to it; nothing drives engagement like fear, anger, and hate; and nothing drives fear, anger, and hate like narratives about internal enemies corrupting your country. People are freaking out about corruption all the time. It’s a lot for a democratic society to bear.

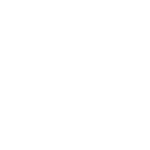

Unfortunately, there’s another problem with narratives of corruption being everywhere—which is that it can create a kind of interpretive smog, making it harder for us to see the worst forms of corruption right in front of our noses: Around the world, literal dictators and the autocratic governments they run are appropriating their countries’ wealth and using it to buy power and influence in democratic countries.

It’s been happening for years. It’s been getting worse. And now, it’s getting worse still. As we go to press with this, The Signal’s second print extra, new leadership in the U.S. Department of Justice is significantly scaling back anti-corruption enforcement—dropping high-profile corruption cases, firing anti-corruption prosecutors, and disbanding efforts to enforce sanctions against Russian oligarchs. An executive order from the president is meanwhile formally suspending the application of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, the landmark 1977 law that prohibits Americans from bribing foreign officials.

Corruption may be everywhere, because human beings are everywhere. But if we want to see it in real proportions, not just as our political biases want us to see it, we have to be able to follow real clues—not least, the money. And in 2025, that’s only getting tougher and more urgent.

—John Jamesen Gould