By Allison Braden & Félix Maradiaga

What is financial repression? Félix Maradiaga on how autocratic regimes are using the global banking system, international law, and new technologies in an old struggle to suppress dissent and hold power.

After Félix Maradiaga’s father died in a traffic accident, his mother, a high-school teacher, worked also as a merchant with a small store to keep things solvent for her family. In the circumstances, it was a difficult decision for her, but when Félix was 12, she sent him from their home in Nicaragua to the United States with a few U.S. dollars tucked into the lining of his shoes; the ruling Sandinistas had confiscated the rest. For a time, Félix lived in a refugee facility, before a Nicaraguan family in South Florida took him in for two years. When he eventually returned home, he intended to build back what the regime had taken from his family—and he did, for a while. But then he got into politics.

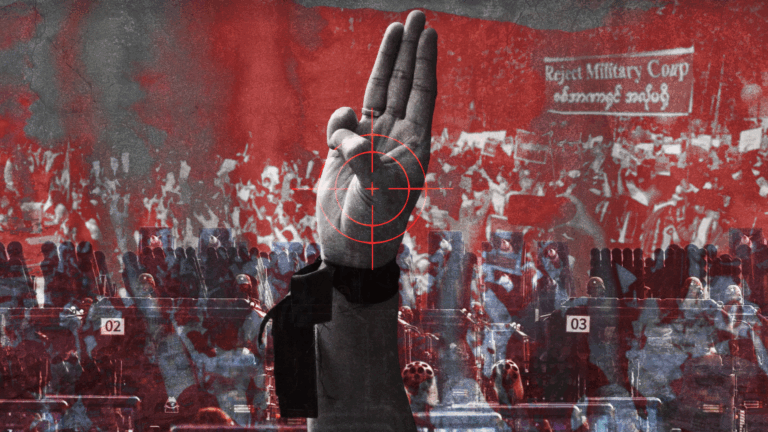

As Maradiaga became more prominent in Nicaragua’s democratic opposition, the regime started moving against him. In 2021, he announced he’d run against President Daniel Ortega. Soon after, he was arrested and confined to the brutal conditions of a Nicaraguan maximum-security prison for almost two years. The Ortega regime subsequently expelled him back to the United States, but not before revoking his Nicaraguan citizenship and confiscating his assets. Since then, the regime has maneuvered to keep him locked out of the international banking system, monitoring and confiscating the assets of his extended family, too. Which is to say, they’ve subjected Maradiaga to methodical financial repression.

For as long as there’ve been autocratic regimes at all, they’ve used financial means to silence dissent and tighten their hold on power. But the techniques of financial repression that the Sandinista government has used against Maradiaga in Nicaragua are in some ways new—and those that dictators are using against their populations around the world continue to evolve. So how does financial repression work today?

Beyond his entrepreneurial and political work, Félix Maradiaga was the secretary-general of Nicaragua’s Defense Ministry, from 2002 to 2006, co-founded the Civil Society Leadership Institute, and has co-authored a number of books about the attrition of democracy in Latin America. Maradiaga says that as technology has changed, so have the tactics of financial repression. New international laws against money laundering, for instance—seemingly straightforward on their face—have given dictators new ways to silence critics. Autocracies like Russia, China, and Iran are meanwhile increasingly collaborating with one another to extend the reach of their repression efforts. And yet activists now have better technology, too. They can use Bitcoin, encrypted communications, decentralized platforms, and even AI-driven organizing strategies to get around the state’s new surveillance methods. The balance of power is still with the autocrats, Maradiaga says, but it’s at least a real fight …

Allison Braden: When we hear about autocrats using financial means to repress dissidents, what exactly are we hearing about?

Félix Maradiaga: We’re hearing about the use of the financial system—more specifically, the banking system—to target people. Which can happen in a lot of different ways. The simplest is to access people’s information. When targeting scholars or think tanks or nonprofits, for example, dictators can find out who the donors are. For human-rights lawyers, the same dictators can find out who the clients are. They can target the money.

Today, financial systems are integrated internationally, so autocrats can use sophisticated methods to target money. They can figure out your location or, say, where you bought a plane ticket, assuming you used your credit card to buy it.

Banks are regulated domestically, but they have to comply with international regulations. Which are, understandably, very tough on money laundering. And so what have autocrats done? They’ve learned how to use anti–money-laundering laws—AML, as they’re sometimes called—for their own ends.

A few decades ago, if you were a human-rights defender and you fled your country to work from abroad, typically you could continue to do that with very little interference from your home country. But autocrats have figured out that by using AML—by labeling you as someone corrupt and involved in money laundering or terrorism or drug trafficking—they can put you on a list. That’s the most sophisticated and concerning part of all this: Today, financial repression at the highest level isn’t just surveillance—collecting and leveraging your data and private information—but the deep manipulation of international anti–money- laundering laws.

"Today, financial repression at the highest level isn’t just surveillance—collecting and leveraging your data and private information—but the deep manipulation of international anti–money- laundering laws."

Braden: And it all relies on control over or access to people’s bank accounts?

Maradiaga: The banking system is the primary tool, but remittances and companies are also targeted. Real estate is targeted.

I now use the expression “financial and asset-based repression.” It’s more comprehensive. Asset- based repression has to do with private property. Confiscation has been used against dissidents for millennia. The Romans, medieval powers, more recently the Sandinistas or the Soviets—they’ve all targeted people’s property.

Braden: So how do you understand the goals of financial and asset-based repression?

Maradiaga: The goals are to neutralize political, civic, and social opposition while undermining critics’ economic autonomy, and ultimately, it’s to prevent dissidents from being able to survive—literally, from being able to buy food or meet their basic needs. As a dissident, financial and asset- based repression means not only that you can’t get a bank account or buy property; it means that you’re a person without any economic freedom—which undermines every other freedom you might otherwise have, too.

Braden: What are the specifics of how autocrats use financial and asset-based repression? How do they do it?

Maradiaga: They have so many methods. The most important and widespread is financial surveillance and the violation of banking privacy.

I was the senior vice president for strategy with Western Union in Central America, so I know a lot of people in banking. When I ask bankers why they allow these regimes to access clients’ data, they say, Well, we’ll be paralyzed here if we don’t obey the judge or the attorney general.

So regimes get access to banking data, including credit-card transactions, banking records, savings accounts, and any financial flows that can be monitored by financial-intelligence units—the organizations that countries set up to monitor money laundering. These units are supposed to stick to this mission, track organized crime, and make sure criminal groups can’t access the financial system.

But they also enable regimes to track dissidents’ transactions and financial activity in real time, both domestically and internationally. So you see, they can block international money transfers. The Sandinista regime in Nicaragua targeted my think tank in 2018, for example, in exactly this way. The regime’s been able to shut down around 5,700 nonprofits by manipulating the country’s financial- intelligence unit. And the International Monetary Fund has honestly been complacent about it; they’ve just looked the other way.

Another method uses the judicial system. By accusing dissidents of money laundering or illicit financing for terrorism, or for some other illegal thing, dictators can get court orders to freeze and close accounts. Then your name gets circulated into an international system that makes it impossible to open a bank account in Europe or the U.S. Until recently, I couldn’t open a bank account in the U.S., myself. Three banks shut down my accounts because I was labeled in the system as a terrorist. This weaponization of the judicial system has a very direct financial impact.

"Until recently, I couldn’t open a bank account in the U.S. Three banks shut down my accounts because I was labeled in the system as a terrorist. This weaponization of the judicial system has a very direct financial impact."

A third method—probably the oldest—is confiscating financial and physical assets. Autocratic regimes can take your land, your house, your businesses, and any other tangible resources. Here, too, they justify these appropriations in reference to anti–money-laundering laws or national-security regulations.

And there’s another method, still: the manipulation of national and international financial institutions, and of the Financial Action Task Force—the FATF—an inter-governmental organization that monitors international transactions for illegal activity. So autocratic regimes use regulations to co-opt national financial institutions—like banks, central banks, and finance ministries—but also international organizations. This lets them block domestic accounts, as well as access the global financial system, cutting off the possibility of dissidents receiving donations, conducting international transfers, or even handling basic transactions. Usually, regimes targeting political dissidents use one combination or another of all these methods.

Braden: How do you see them having changed over time?

Maradiaga: In the digital age—and with the integration of global financial systems—dictators have found more and more sophisticated ways to repress their opponents. In Nicaragua, for example, the Sandinista regime has learned how to use FATF regulations to freeze funds—which they’ve done with as much as US$300 million—for churches, universities, and dissidents.

But this sort of thing certainly isn’t limited to Nicaragua. Countries like Venezuela, Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan are using FATF regulations to exclude opposition members from global financial systems.

These regimes are becoming more integrated, too—and that’s really concerning. The central bank of Nicaragua, for instance, is working with the central bank of Russia and other autocratic countries to share our data. Iran is working very closely with Venezuela. Russia is working very closely with China. And they’re all learning very fast how the West’s international banking rules work—so they can bypass the rules to avoid sanctions and repress dissidents. People in the democratic world don’t really understand how deep, vicious, and commonplace this kind of collaboration is—especially among China, Iran, and Russia.

And then there’s artificial intelligence. Which China is getting particularly good at using for financial repression. It allows them to target dissidents in new ways. It used to be, if you wanted to do that methodically, you needed a lot of capacity—say, to comb through a nonprofit’s financial records or a university’s research, or a think tank’s publications, or a human-rights organization’s reports. Now, a regime can do all these things at superhuman speed using AI. It’s quite frightening.

"Autocratic regimes now have tremendously precise instruments of repression, real-time financial surveillance justified under anti-terrorism laws, and cross-border cooperation through financial-intelligence units."

Braden: Which regimes would you say have been using these tools to the greatest effect?

Maradiaga: China and Russia. It’s harder to find evidence of China doing it, because China tries to put up a front of legitimacy in the international system. They tend to be very careful to avoid harming their reputation. Russia, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Belarus, and Kazakhstan do it more openly. It’s almost impossible for dissidents to operate in any of those countries. Cuba and North Korea don’t have private banking systems, so they’re different in that sense.

Braden: How successful are these financial and asset-based repression efforts?

Maradiaga: Very successful. Financial and asset-based repression has become one of the most effective sets of tools in the world for silencing dissent. The repression of dissidents is no longer just about prison. It’s no longer just about forced exile. Today, dissidents face near-total economic exclusion, as in my case. The Ortega regime in Nicaragua didn’t only confiscate all my assets, including the assets of my extended family and the nonprofits I led; they had me placed on an international watch list, and to this day I face restrictions that prevent me from operating normally within the banking system. I’ve spent substantial personal resources trying to clear my name—and I’m a relatively sophisticated user of the financial system as a whole.

But I’m far from alone. Hundreds of dissidents from Nicaragua, Russia, Belarus, and other countries have faced similar treatment.

What’s most troubling is that none of this repression would be nearly as effective if not for the indifference—or even the unintentional complicity—of the international banking system. Mechanisms originally designed to combat money laundering are being manipulated to justify the financial exclusion of pro-democracy activists. The FATF regulations have been weaponized. Meanwhile, banks in democratic countries often refuse service to dissidents from autocratic countries simply because the regime at home has labeled them as foreign agents. These banks know we’re not corrupt people, but it’s extremely difficult to have you as a client if you’re officially a terrorist.

Braden: On balance, would you say new technology has made it easier for autocrats to implement financial repression, or has it also helped dissidents avoid financial repression in any significant ways?

Maradiaga: On one hand, autocratic regimes now have tremendously precise instruments of repression, real-time financial surveillance justified under anti-terrorism laws, and cross-border cooperation through financial-intelligence units. But on the other hand, dissidents have access to a growing arsenal of what we’ve come to call “freedom technologies”—technologies such as Bitcoin, encrypted communications, decentralized platforms, and even AI-driven organizing strategies.

"Dissidents have access to a growing arsenal of what we’ve come to call “freedom technologies”—technologies such as Bitcoin, encrypted communications, decentralized platforms, and even AI-driven organizing strategies."

A tool like Bitcoin is a lifeline. There’s a long way to go, particularly in the capacity to transfer it to dangerous places in the world, but it gives us hope, because it’s among the few remaining ways we can receive donations and continue to fight against dictatorships. So these technologies are giving us an edge—but the playing field is still very unequal. Dictators adapt—but so do we. We’re building networks across borders. We’re learning from one another. We’re using technology not just to survive but to organize and fight back. We no longer live in a world where tyrants operate entirely in the dark. Thanks to contemporary technology, we can shine a light on them—and sometimes that light is just bright enough to keep resistance alive.

Braden: How do you see this emerging autocratic repertoire for financial and asset-based repression relating to some of the things dictators do more on the macroeconomic level—like nationalizing banks or manipulating capital controls? Are those part of financial and asset-based repression?

Maradiaga: They’re related as violations of economic freedom. Currency manipulation, artificial inflation, or kleptocracy and corruption— these all weaken national economies for political purposes. But they don’t specifically target dissidents; they’re more widespread attacks on the economic freedom of the general population. The two dimensions are connected, though: Central banks going against the economic freedoms of the general population and autocrats using the banking system to target specific dissidents are, I think you’d have to say, part of the same evil.

Braden: What was your experience with financial and asset-based repression in Nicaragua?

Maradiaga: Yes, for me, this kind of repression isn’t an abstract concept. It’s deeply personal. Sandinista militants ransacked my mother’s small store in 1985. They took everything she’d built on the excuse that she was operating outside state control. Later, they devalued the currency overnight, and my family and my community lost all their savings. We went from a nice lifestyle as middle-class businesspeople to nothing. When I was 12, I fled the country alone.

Years later, when I was back in Nicaragua, I became a successful entrepreneur, a renewable-energy engineer, and a top executive in the private sector— and I was able to build some wealth. But when I forced myself from the relative comfort of the private sector to oppose the autocracy in my country politically, they confiscated my property again—and not just mine; they also confiscated the assets of my extended family. They closed my bank accounts. They labeled me a terrorist. They took my property and put me on an international blacklist.

Even now, after being in exile and stripped of my citizenship, my family in Nicaragua is still punished. Just a few days ago, I got the news that because of my public advocacy, another family member of mine has lost her property. My mother’s home in Nicaragua was also confiscated last year. And we’re not allowed to send or receive any money through normal banking channels.

So when we talk about financial repression, we’re talking about the systematic destruction of the things that give people dignity and independence in their lives. It’s about silencing you—not just with fear but with poverty. Yet so far, we’ve kept finding ways to survive, rebuild, and resist.