Brendan Hasenstab & Roger Huang

Why are countries around the world developing virtual legal tenders? Roger Huang on the origins, implementation, and implications of central bank digital currencies.

As dictators and dissidents refine new measures and countermeasures for seizing or securing money and assets in their ongoing struggle with one another, governments around the world have been developing the technological basis for what’s almost the conceptual opposite of the decentralized cryptocurrency Bitcoin: a kind of digital currency that’s centralized not just in a private company but in the state itself.

Central bank digital currencies—CBDCs—aren’t entirely new. Prototypes go back to the 1990s. While early iterations had all kinds of differences among them technically, they all shared the common theme of extending a government’s control over money and payments.

Since 2019— the year Facebook announced its stablecoin project, Libra—a number of countries have introduced CBDCs, including China, India, and Russia. A few have even taken aggressive measures to drive CBDC usage, as Nigeria did by creating a cash shortage in 2022 or the Bahamas did by announcing in 2024 that banks would soon be forced to distribute their CBDC. Now, more than 135 jurisdictions in the world are either developing, piloting, or launching CBDCs—with several already making them available to the public.

Why are they doing this?

Roger Huang is a freelance journalist and the author of Would Mao Hold Bitcoin? Huang says the logic of central bank digital currencies is a technocratic one that can take a very different form between democratic and autocratic states—one shaped by the limited mission of central bankers; the other, by the systemic will to power of authoritarians. Yet in either case, CBDCs represent a fundamental shift in any financial system that would adopt them, creating direct relationships between citizens and central banks—and so, an extraordinary platform for governmental control.

Which, Huang says, accounts for early patterns of resistance to CBDCs in democratic societies: While their central bankers might tend to see CBDCs as innovations that can support financial inclusion, payment efficiency, global competitiveness, and enhanced monetary-policy tools, citizens who’ve been consulted on them have shown a lot of skepticism. And where CBDCs have been implemented, adoption has been slight. Huang thinks these patterns have a logic of their own: Throughout the democratic world, there’s a widespread, deep reluctance to support any measures that would establish significantly more bureaucratic state power over people’s lives— meaning there’s now an unresolved tension between the technocratic logic inclined toward these digital currencies and the democratic logic inclined away from them …

Brendan Hasenstab: What is a central bank digital currency, and how does it work?

Roger Huang: A CBDC is a digital version of a national currency and a direct liability of a country’s central bank—unlike regular bank deposits, which are claims on private banks. This represents a fundamental reset in the relationship between an individual and the financial system they live in— establishing a direct connection between citizens and central banks.

CBDCs typically operate through smartphone applications. In countries with active implementations, like China’s e-CNY and Nigeria’s eNaira, people access their digital currency through mobile apps similar to the way they do with payment platforms like WeChat Pay or Venmo. The process is fairly straightforward: Users download the app, verify their identity, connect accounts, and can then make payments by scanning merchant QR codes or entering recipient addresses.

To be clear, this would describe what are called retail CBDCs, which are for everyday consumer use. There are also wholesale CBDCs, which are restricted to financial institutions for interbank settlements. So there are two models of CBDC; they work in parallel.

But while CBDCs are digital versions of national currencies, they’re not simply that; they’re different from traditional money—or even cryptocurrencies—in a consequential way: They give central banks unprecedented control. For instance, Chinese authorities can program their digital yuan with expiration dates, forcing spending within specific timeframes. Central banks also maintain control over all transaction data and select all the vendors serving the CBDC ecosystem.

"CBDCs are digital versions of national currencies, but they’re not simply that; they give central banks unprecedented control."

As you can imagine, this centralization creates significant cybersecurity considerations. The responsibility for data security shifts from multiple private institutions to a single government entity—raising concerns that are already not just theoretical, after incidents like the 2022 Shanghai Police database leak that exposed 1.3 billion personal records.

Hasenstab: Where did CBDCs originate?

Huang: You can trace them back to the 1990s in Finland, with important developments emerging in China and Ecuador in 2014. But the big catalyst for widespread CBDC development came in the summer of 2019 when Facebook announced its Libra stablecoin project. That triggered something close to panic among policy makers and central bankers, who feared losing their monopoly on money issuance to a private company—which could potentially cause currency substitution on a global scale. Almost overnight, CBDCs transformed from conceptual frameworks into urgent priorities for governments worldwide.

While cryptocurrencies, including Bitcoin, played a role in demonstrating the possibilities of digital currencies, some countries were already moving away from cash independently. China, for instance, transitioned from being one of the heaviest cash users in the world to being minimal cash users within a single generation, helping prep the ground for CBDC adoption there.

Since 2019, CBDCs have evolved rapidly from more passive, conceptual projects to active, practical implementations. As of today, over 135 jurisdictions are exploring or implementing CBDCs. And those jurisdictions represent more than 98 percent of the global economy. Adoption rates are still generally weak, but a number of countries—including China, India, Russia, Nigeria, Jamaica, and The Bahamas—already have public-facing CBDCs.

Hasenstab: How have autocratic governments been using CBDCs, as compared with democratic governments?

Huang: Autocratic governments have embraced CBDCs more aggressively than democratic ones, using these digital currencies to enhance surveillance capabilities. In China, even the lowest- privacy tier of their digital yuan requires phone- number verification linked to real-world identities, creating a system where all users are identifiable by default. Chinese authorities have meanwhile banned alternative digital currencies like Bitcoin or Tether. So now you’ll get arrested there for transacting in any of them.

Overall, across autocracies and democracies, jurisdictions allowing central banks greater autonomy have seen faster CBDC adoption. India, for example, is still a democracy, but Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s deference to the central bank has accelerated the development of the digital rupee. In places like the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, or European Union, though, governments have moved more cautiously, recognizing the need for legislative oversight. In the U.S., the chairman of the Federal Reserve, Jerome Powell, has said explicitly that the Fed would need congressional approval to launch an American CBDC.

"Autocratic governments have embraced CBDCs more aggressively than democratic ones, using these digital currencies to enhance surveillance capabilities."

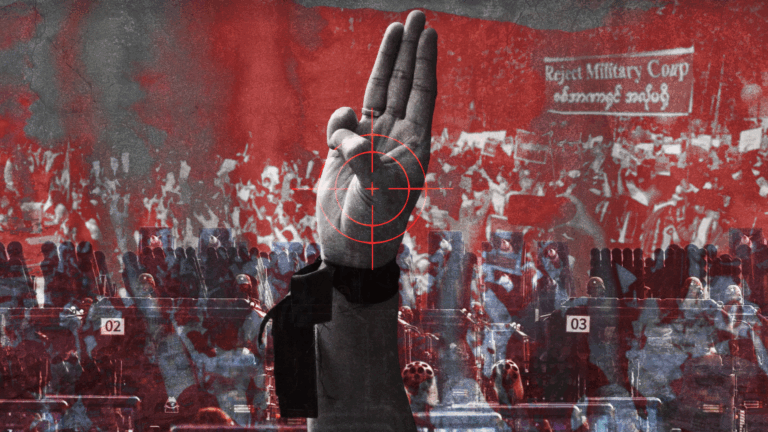

But the way autocratic governments have been using CBDCs—not least in China—illustrates concerns about how they could potentially be used even by democratic governments. The risk is that they could enable sweeping financial surveillance, restrictions on transactions, the freezing of funds, and other potential abuses of power. This isn’t just theoretical, either. Both autocratic and democratic states have already used financial systems to target protesters—from the Hong Kong freedom demonstrations in 2019-20 to the Ottawa trucker protests in 2022.

Hasenstab: You say adoption rates have generally been weak—why is that?

Huang: It looks like there’s a certain fundamental disconnect between central banks’ aspirations and public acceptance. In open societies, when citizens have been consulted directly about CBDCs, they’ve often expressed strong opposition.

The Bank of Canada’s experience may be a telling example: When it conducted public consultations, the vast majority of Canadians polled across the country’s political spectrum rejected the concept, and so the BoC ultimately decided against issuing a digital Canadian dollar. You can see a similar pattern of skepticism across other democratic societies. And you can see that pattern reflected in institutional caution.

To the extent that we understand this pattern, it seems intuitive: There’s widespread concern about privacy. Financial-transaction data offers an extraordinarily intimate view into people’s lives—showing what they value, where they go, who they associate with, even what causes they support. And a lot of people seem to recognize this.

There are also concerns about government overreach that mightn’t come directly to mind for some people living in democracies but that wouldn’t be too difficult for them to imagine, either: CBDCs can enable a government to put expiration dates on funds to force spending, put restrictions on specific kinds of purchases, automate fines or negative interest rates, freeze or seize assets, and so on.

Again, if you want to see the full potential for government overreach, you can look at China. There, in the existing system, people who’ve lost certain kinds of court judgment are prevented from buying airplane or train tickets. With CBDCs, a restriction like that would be more directly enforceable, since the government would now control the payment method itself rather than just regulating private intermediaries.

Hasenstab: Presumably, policy makers and central banks haven’t argued for this kind of digital currency simply, or even mainly, in terms of the control it gives them. How do they articulate the potential benefits of CBDCs for their societies?

Huang: In a few ways. One is in terms of financial inclusion. By providing a digital form of currency accessible through smartphones, some argue, CBDCs could extend basic financial services to people currently excluded from traditional banking. There’s also the idea that CBDCs would enable payment-system improvements—like faster and more efficient transactions, streamlining them and reducing friction, potentially lowering costs for consumers and businesses.

"Financial-transaction data offers an extraordinarily intimate view into people’s lives—showing what they value, where they go, who they associate with, even what causes they support. And a lot of people seem to recognize this."

Some central banks argue, as well, that CBDCs would enhance their state’s financial positioning globally—that they’d help the country maintain and develop national competitiveness in a rapidly changing international monetary landscape. Some argue that they’d enhance cross-border payments—given how slow and expensive traditional international transfers can be. And some argue that CBDCs represent beneficial new tools for implementing monetary policy. From a central banker’s perspective, that could mean more precise ways to influence consumption patterns, employment rates, or overall economic stability.

Hasenstab: What do you make of these views?

Huang: I recognize the sense they can make from a certain perspective—but I also think they illustrate a real tension between the technocratic vision of many policy makers and central bankers, on the one hand, and the idea of democratic oversight that makes the democratic world democratic, on the other.

Central bankers, in particular, tend to be appointed rather than elected officials. So it may be more natural for them to think like philosopher-kings and imagine CBDCs as logical extensions of their mandate to manage national economies. From this perspective, CBDCs represent new tools that could help them fulfill their mission of maintaining sound currency and promoting employment.

But across democratic societies, there’s a lot of popular discomfort with the idea of unelected officials gaining significantly expanded powers. Which I think is what you see in the lackluster adoption of CBDCs worldwide—and in the positive resistance to them in countries with strong democratic traditions, as we saw in Canada.

So I think there are already signs of an almost visceral reaction to the idea of central bank

digital currencies—where people may not even understand what these things are particularly well, at this point, and yet brace at them quite exactly for what they are. It appears broadly intuitive to people that they should be very uneasy with their government having the kind of access to them and control over them that CBDCs would enable.

That’s a real tension—but it also has the potential to drive a vicious-cycle dynamic: If you try to force people to adopt something they’re uneasy with, because they’re anxious about the power it would give you over them, the whole thing risks confirming the very concerns about coercion and control that touched off their resistance in the first place.