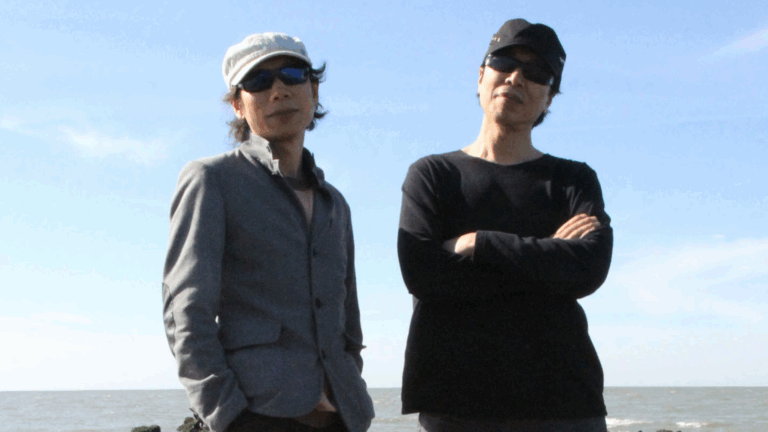

Gustav Jönsson & Farida Nabourema

Why has Bitcoin become so popular with dissidents living in dictatorships? Farida Nabourema on what the emerging technology has in common with an old suitcase stuffed with cash.

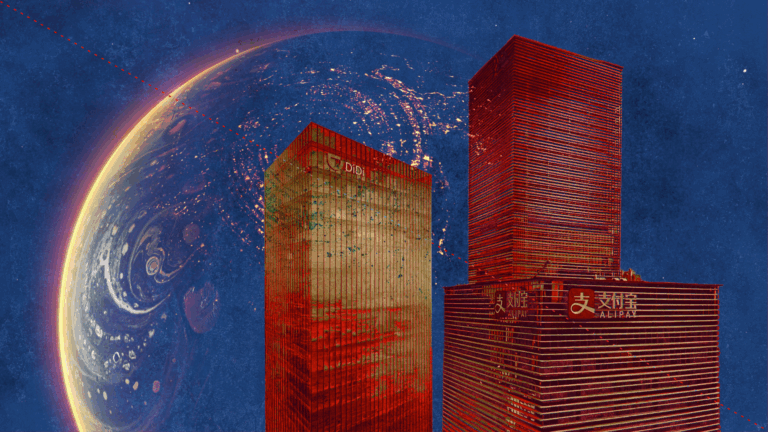

Autocratic regimes are developing a repertoire of tactics for financial repression—or as Felix Maradiaga prefers to say, financial and asset-based repression—to clamp down on and fundamentally incapacitate dissidents and pro-democracy activists in countries around the world. Dictators will freeze people’s bank accounts and seize their assets, sometimes using global financial and legal institutions—and often new technologies—to do it. All of which they’re only getting savvier with.

At the same time, people in autocratic countries are figuring out new ways to fight back. Some have used emerging digital assets, notably Bitcoin, to fund their organizations and movements in ways that make it easier to circumvent government control. As an example, the team working with the late Russian opposition politician Alexei Navalny took in several million U.S. dollars worth of Bitcoin—a little more than 10 percent, they say, of their total funding.

Why does Bitcoin, of all things, seem to have become so important to dissidents in autocratic countries?

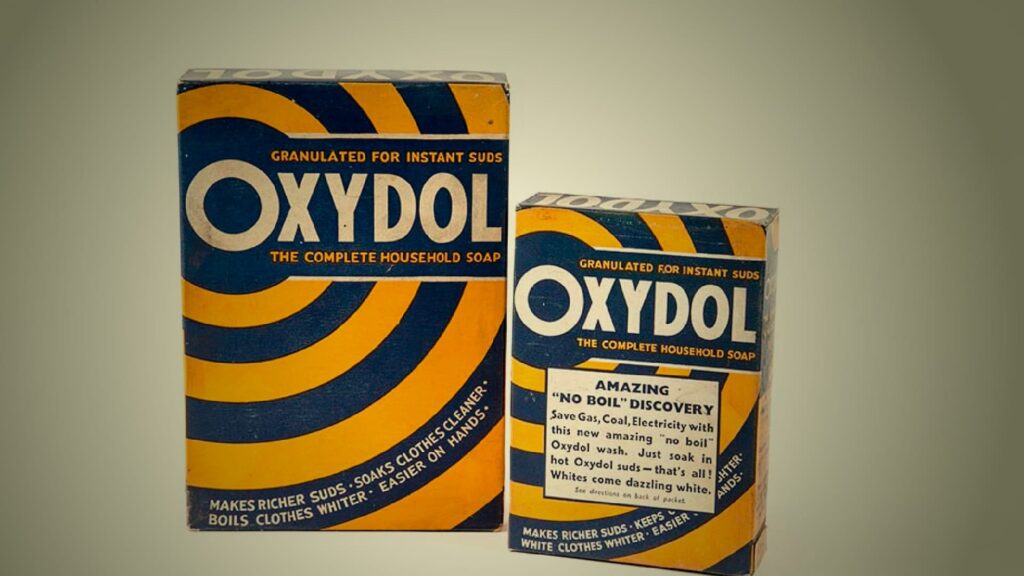

Farida Nabourema is a Togolese democracy and human-rights activist, and the executive director of the Katutu Civil Rights Center. Nabourema says that while Bitcoin relies on new technology, it’s best understood as just one of the latest in a long series of innovations in the long struggle between autocrats and dissidents: Back in her father’s time, the opposition would smuggle cash into Togo in suitcases or detergent boxes. Now, they get Bitcoin.

The biggest difference, Nabourema says, is that Bitcoin is easier and safer to use, which counts for a lot. Once upon a time, Togolese activists would have to send a courier to Ghana to stuff cases with cash; today, they can now transfer funds with the push of a button. That’s not just reduced risk around transactions; it’s helped build trust between those who send the funds and those who receive them. And for embattled dissidents, trust is of the utmost importance: If you can’t trust your comrades, you’re unlikely to risk prison or even torture for opposing the government. In a sense, building trust in a climate of fear is what keeps civil society alive in despotic states.

Nothing stays safe in these places for long, though. Dictators are doing everything they can to disrupt dissident activities, planting spyware on phones and computers to try to stem the flow of Bitcoin …

Gustav Jönsson: Most people in the West know of Bitcoin as a speculative asset. How has it become a tool for dissidents in autocratic states?

Farida Nabourema: People living in autocratic states turn to Bitcoin for a number of reasons. One is that it helps bypass financial repression and surveillance, especially in countries like mine, Togo, where we’ve been fighting a dictatorship that’s ruled for 59 years.

The government targets activists by freezing bank accounts and monitoring money sent through traditional remittance routes. Some of our comrades were arrested for sending money to the movement after returning to Togo from the diaspora. After six years in jail, they were handed 10-year sentences—on false charges of funding “terrorism.” That’s a theme, as you’ll see.

It became clear that if we wanted to resist the regime, which is trying to block these traditional funding channels, we needed a new solution. We had to raise funds from the diaspora—but securely. In the past, we used to send money to neighboring countries like Ghana and then have someone collect it and bring it back physically. As you can imagine, it was very risky for both the middlemen and recipients. Anonymity wasn’t guaranteed.

But since we started using Bitcoin in 2018, that’s changed. Now, we can receive Bitcoin, exchange it through local platforms, and cash it out—all without drawing suspicion. Which protects both the sender and the recipient. And that’s helped build significant trust with donors from the Togolese diaspora. Before, people feared the money could be traced back to them, potentially putting them and their families in real danger. Today, they can give without even us knowing who they are.

"We used to send money to neighboring countries like Ghana and then have someone collect it and bring it back physically. As you can imagine, it was very risky for both the middlemen and recipients."

Jönsson: What kinds of things are you financing this way?

Nabourema: We use Bitcoin to give some of our imprisoned comrades monthly payments to cover food and medical care. Many of them have been tortured by government officials and kept in horrific conditions. After being trapped in tiny cells for months on end, some can no longer walk or stand on their own. The cells are so small that prisoners can only sit or lie down. Some have suffered ruptured knees; others have sustained severe leg injuries or even lost their mobility entirely.

These conditions have been documented by the World Organisation Against Torture, which we partner with to visit detainees. Many require ongoing medical care, and unfortunately, the state offers no support, leaving families responsible for funding their health care in prison. But many of those families are poor, so we do what we can to help cover the costs of medical attention, medication, and food.

We also support local journalists. The regime targets independent outlets by pressuring private companies not to advertise with them. As a result, these journalists constantly struggle to finance their work. We’re able to support some of them.

And we run awareness campaigns in rural communities, distributing printed flyers that explain key issues we want people to understand and act on. One recent flyer focused on access to clean water. More than 70 percent of people in Togo lack it; in rural areas, it’s 95 percent. After the campaign, we encouraged communities to push for action. Just last month, some villages held protests demanding government action on clean- water access.

These are the kinds of projects we fund. Bitcoin allows us to do it securely, without endangering more people—while also building crucial trust among grassroots organizers and donors.

Jönsson: How do people send and receive Bitcoin?

Nabourema: At the organizational level, we use a multi-signature Bitcoin wallet that enables people to donate funds externally and our team to contribute internally. Using a multi-signature wallet means that multiple people have to approve any transaction, as a way to increase security and prevent theft or detection.

Before sending money, we first run training programs to teach recipients how to use Bitcoin. Our organizers go through a program focused on digital and financial security. That’s because our government frequently uses digital spyware. Several members of our movement have had spyware planted on their phones and computers. So we require everyone to complete this training, after which we provide them with new devices.

"We can receive Bitcoin, exchange it through local platforms, and cash it out—all without drawing suspicion. Which protects both the sender and the recipient. And that’s helped build significant trust with donors from the Togolese diaspora."

We also partner with a cybersecurity organization to conduct forensic checks and ensure their devices are free of spyware. We run these training camps in Togo, where we teach participants how to use Bitcoin, download wallets, and which trading platforms they can use to convert it to local currency.

Once they sell their Bitcoin, they typically get paid through mobile money, which is widely used across African countries. It works like a mobile wallet, where your phone number functions as your bank account. They sell Bitcoin through a platform similar to Cash App, but it’s integrated with their mobile provider.

You can think of it as comparable to a mobile wallet in the U.S. or Europe, like Apple Pay or Google Pay. They sell it on a platform and receive mobile money directly. Once the funds arrive in their mobile wallet, they can use the money however they want. Even prisoners can receive funds; because of corruption, guards can be bribed to smuggle phones into prisons—so inmates can directly access their money while behind bars.

Jönsson: Why Bitcoin over other cryptocurrencies?

Nabourema: In our case, we sometimes use the stablecoin Tether—USDT, as it’s called in reference to its currency code—which is pegged to the value of the U.S. dollar. Some donors prefer to contribute in USDT. We accept only Bitcoin and USDT—but mostly Bitcoin, because it offers a stronger sense of security. Most other cryptocurrencies are centralized, meaning the government of Togo could pressure their platforms to hand over user information.

The same is true for cryptocurrency exchanges. Take Binance, for example—a company we advise our members emphatically to avoid. In several countries, Binance has handed over user data to governments, which has put people’s security at significant risk. That’s why we prefer using safer platforms, especially Bitcoin. They simply offer greater protection.

Jönsson: Where do you see dissidents using Bitcoin to particularly notable effect?

Nabourema: In my experience, I see they using it widely across the African continent.

In 2020, for example, during the End SARS protests against police brutality in Nigeria, activists turned to Bitcoin when the government began freezing their bank accounts. They raised hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of Bitcoin.

There’s meanwhile a war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which has led to a large- scale displacement of civilians—and people have been using Bitcoin to raise funds for supporting the DRC’s displaced communities. Across the continent, Bitcoin has become a more and more common tool. I know dissidents who’re using Bitcoin in Uganda, Zimbabwe, Eritrea, and Somalia.

Jönsson: Do you know of any dissidents who don’t want to use Bitcoin for any reason?

Nabourema: Honestly, I’ve never spoken to a dissident who wasn’t enthusiastic about the idea of using Bitcoin. Every dissident I’ve introduced it to has been excited and eager.

"Once dissidents sell their Bitcoin, they typically get paid through mobile money, which is widely used across African countries. It works like a mobile wallet, where your phone number functions as your bank account."

There’d just be one near-exception—a friend of mine from Kenya. She’s more of an environmental activist, not someone focused on overthrowing a government. And she’s had concerns about Bitcoin’s energy consumption. She’s the only one I’ve spoken with who’s taken more of a critical view.

Others were skeptical at first because they didn’t understand how the technology works. They assumed it was just another online scam. Some didn’t even believe Bitcoin was real. But once I explained it, they became extremely interested. The thing is, dissidents fighting authoritarian regimes are constantly trying to protect their privacy and safety. You’re up against a whole government trying to bring you and your movement down in any way they can. So you’re quick to embrace any tool that helps you avoid that.

But even though Bitcoin is made possible by new technology, I don’t see it as a fundamentally new idea. Dissidents have always found ways to smuggle money. Take my grandfather for instance. He was an activist against the French colonial regime. He was imprisoned twice, once for nine months and then again for seven. And the reason he was jailed was simple: The French imposed harsh taxes on farmers. They had to pay their taxes on crops, which meant they didn’t have enough left to feed their families. They were essentially working for the colonial government for free. And if you didn’t meet the tax quota, you’d be publicly beaten, even whipped, or jailed.

So my grandfather and others in the community decided to stop farming entirely. If you’re not a farmer, they can’t tax you—so they gave it up and lived by hunting. Later, they heard about the independence movement in the capital, about 170 miles from their village. When they contacted people in the independence movement, they were told they needed funding.

So they returned to farming just to raise money for the movement. But they had to do it secretly so the colonial authorities wouldn’t know they’d started up again. They worked on each other’s farms as “slaves”—because slaves weren’t taxed. And instead of paying taxes, they funneled their money into the independence movement. My grandfather and a friend would walk to the capital to deliver the money and then return. Each round trip took three weeks. Which just shows that figuring out innovative means of funding anti-autocratic resistance is nothing new.

"Bitcoin offers a strong sense of security. Most other cryptocurrencies are centralized, meaning the government of Togo could pressure their platforms to hand over user information."

In my father’s time, when he took up activism in the 1970s and 1980s, the regime allowed a system they called “mandates.” In the U.S., this would be like going to a post office and buying a money order— basically, prepaid checks issued by the postal service. Back then, these money orders could only be picked up at the post office. So members of the diaspora would send money to support dissidents, but the government easily intercepted and confiscated them. Eventually, people had to find a different method, since authorities were searching bags at the airport. So people started buying powdered detergent, which at the time came in cardboard boxes like cereal. They would open the boxes, fold up cash, hide it inside the detergent, and then seal it back from the inside and ship it. When the recipients shook the boxes, it sounded like regular detergent, so nothing seemed suspicious—but when they opened the boxes, they could retrieve the hidden cash.

People always find creative ways to get around restrictions, as with Bitcoin now.

Jönsson: Felix Maradiaga has described Bitcoin as “the only tool that is bulletproof to … financial repression from dictators,” meaning that dictators can’t directly interfere with it. But what risks do dissidents face using Bitcoin?

Nabourema: There are a few. One is that you can lose your wallet or your keys; that’s a real risk I always warn people about. But there are tools available today that help reduce it.

A second is that Bitcoin is private, but not fully anonymous—so if a government is invested in tracing a transaction, and has the right forensic tools, it’s possible they could trace it back to the sender. That would take time and resources, and they’d need to know what they’re looking for in the first place, but the risk is still there.

Then there’s volatility. Most people using Bitcoin for activism don’t hold onto it. They’re not in it for speculation. They usually sell it almost immediately after receiving it. Those who hold onto it long-term usually have no other way to save—unbanked people who can’t open an account or store money safely. In cases like theirs, I’d actually recommend a stablecoin over Bitcoin. If someone doesn’t need the money right away and wants to make a profit, they’ll need to be patient and essentially bet on luck—because there’s no practical way to predict whether it’ll go up or down. It might drop in value right when they need it most. That’s when you’re forced to sell at a loss—when you really need the cash, even though the price has fallen. But if the goal is to fund urgent work, it makes sense to sell right away—and for that, Bitcoin has become uncommonly useful.