In August 2020, Lilia Kvatsabaya, a Belarusian graphic design student, found herself amid the largest protests in the country’s history. She wore a white t-shirt and white pants — symbolizing solidarity with Belarus’ political prisoners — and a red and white bracelet, the colors of the pro-democracy movement. She carried a sign that read: “I’m a Belarusian woman. I have a voice.”

Lilia joined thousands of people in the capital city of Minsk to peacefully protest the fraudulent re-election of Belarus’ brutal dictator, Alexander Lukashenko, who has ruled since 1994 — seven years before Lilia was born. That August day, she and her friend marched with the crowd while keeping a wary eye on the siloviki — the Belarusian security agents, easily identifiable in their body armor and black face masks — who patrolled every major street.

Suddenly, they heard screams and explosions from the front of the crowd, and Lilia knew something was wrong. Soon, people started running as the police fired stun grenades into the crowd.

Lilia was raised in Belarus, a landlocked country in Eastern Europe with a population of 9.3 million. At the time, the country was part of the Soviet Union (USSR), and in 1991, during the dissolution of the USSR, Belarus declared its independence. In 1994, it adopted a national constitution and elected Alexander Lukashenko as the first president.

Over the past 28 years, Lukashenko has solidified his autocratic rule. Elections, which occur every five years, are neither free nor fair. Moreover, the regime goes to great lengths to silence all forms of dissent, including murdering opposition leaders, persecuting independent media and NGOs, and exerting violence against protesters. Artists who are critical of the regime are arrested, tortured, and even killed.

The year 2020 marked the first election in which Lilia could legally vote. She was 19 years old and in her second year at the Belarusian Academy of Arts, learning how to design logos, typography, and posters. Lilia didn’t think about art as a political tool or a way to express one’s opinions, but she was excited to exercise her right to vote.

Lilia could sense rising tension in her country in the months leading up to the election. The people of Belarus were tired of Lukashenko’s corrupt rule, pervasive human rights abuses, and inadequate response to the COVID-19 pandemic. At the height of the epidemic, Lukashenko suggested that citizens drink vodka and rest in the sauna to protect themselves.

As protests against his regime grew, an unlikely leader emerged in Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, the wife of Sergei Tsikhanousky and an organizer of early protests against Lukashenko. Other opposition candidates were imprisoned or chased out of the country, but Sviatlana stayed and united Belarusians around a clear and straightforward message: Belarusians deserve free elections and accountable leadership. Sviatlana’s moral clarity resonated with Belarusians and delivered a shock to the Lukashenko regime, which had scoffed at the possibility of a successful female candidate.

On election day, August 9, 2020, the regime announced that Lukashenko had won in a landslide victory, but the reality was quite different. The opposition had set up a parallel online voting system and, combined with independent reports, could confidently declare that the regime had falsified the election results. This ignited the most significant protest movement in the history of Belarus. It wasn’t just about election fraud — Belarusians were fed up with dictatorship.

The next day, Lilia approached a nearby metro station, where a few hundred people had gathered, demanding Lukashenko’s resignation. Before long, police began arresting peaceful demonstrators, forcibly dragging some into vans and beating others. Lilia remembers hearing explosions and screams as the crowd dispersed in panic.

Similar incidents unfolded across the country. Hundreds of thousands of protesters took to the streets, calling for democracy and an end to Lukashenko’s 26-year rule. The regime responded with excessive force, often using rubber bullets, stun grenades, tear gas, and live ammunition. Over the first few days, they detained thousands of protesters — some were dragged into unmarked vehicles by police dressed in plain clothes — and held them in overcrowded cells under inhumane conditions.

When she wasn’t in school, Lilia worked as a cashier in a pet store. On August 13, just days after the presidential election, a man with bruises on his cheeks and legs entered the store. When he saw that Lilia was wearing her white and red bracelet in support of Tsikanhouskaya, he confided in her, revealing that he had been detained for his protests and tortured by prison guards.

Lilia was horrified at the brutality of the Lukashenko regime, which it sought to hide from the international community. In 2020, the Human Rights Centre Viasna documented more than 33,000 detentions, more than 1,000 cases of torture, and seven protesters killed. Stories like that of the man in the pet store were not unique — and at that moment, Lilia knew that she had to respond.

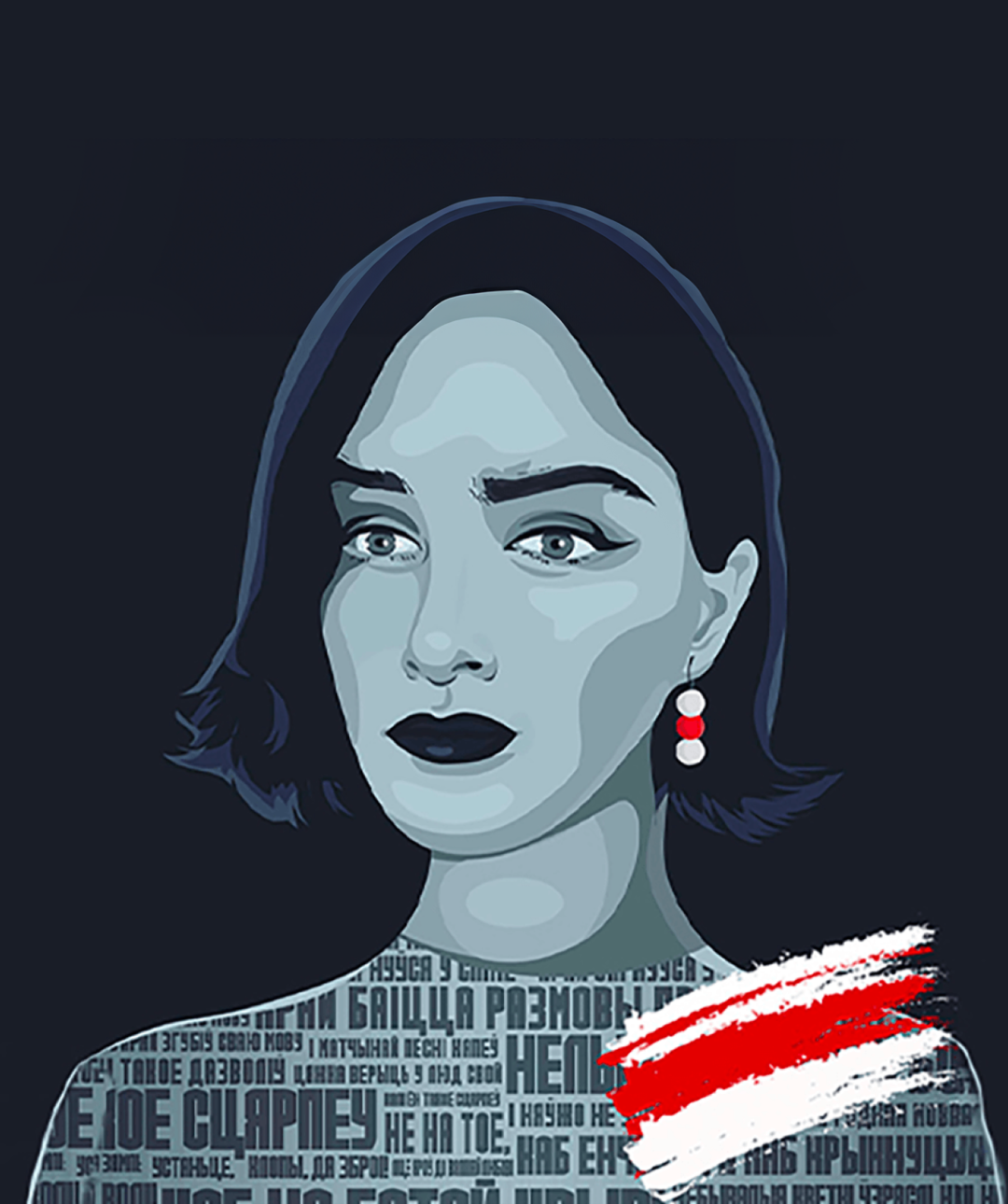

Lilia realized that protesting the regime was more important than simply creating logos in her graphic design courses. She began using her artistic skills to contribute to the pro-democracy movement and spread awareness about the urgent situation in Belarus. Her early pieces celebrated the brave protesters who took to the streets day after day. They also exposed Lukashenko’s weaknesses — such as the regime’s reliance on violence to subvert dissent, its corrupt judicial system, and its financial and political dependence on Vladimir Putin.

As weeks stretched into months, Lukashenko’s regime continued its brutal crackdown on civil society. Regime officers beat protesters, jailed journalists, and levied threats and intimidation at anyone who spoke against the government. The situation was unbearable. In November 2020, Lilia moved to Hawai’i, where her mother had remarried. From there, she continued publishing political art online, finally unencumbered by the looming threat of Lukashenko’s regime.

At the beginning of 2021, HRF invited Lilia to feature several of her pieces in our virtual gallery, In Pursuit of Freedom: A Collection of Global Protest Art. Together, we selected engaging and thought-provoking pieces: one portrayed Alexander Lukashenko melting into the ground, and another depicted Putin using deceit (symbolized by a Pinocchio nose) to punch a hole through the country of Belarus.

Lilia later joined the inaugural class of our Art in Protest Residency, a six-month program designed to help young dissident artists enhance their practice, develop new skills in digital arts, and increase their access to diverse audiences. Since Lilia never had the chance to finish her degree in graphic design in Belarus, she jumped at the opportunity to join the program.

As a resident artist, Lilia engaged in weekly mentor sessions with Niki Selken, an artist and curator from the Gray Area Foundation for the Arts, HRF’s partner organization based in San Francisco. Niki examined Lilia’s progress each week and provided feedback, often sharing resources and examples for inspiration. Niki also helped Lilia publish her first official website and portfolio, which garnered greater exposure for her art, and allowed her to better advocate for Belarusian democracy abroad.

Lilia also attended tutorials and group sessions on digital art with Gray Area artists. At first, she was intimidated — she didn’t have much experience with digital art, especially compared to the tech-savvy artists of San Francisco. But to her relief, the other artists were extremely supportive, giving her helpful feedback and offering to assist wherever possible. One of her peers, for instance, shared a source code for an interactive story-telling project she was planning, saving Lilia the time and effort required to learn a new computer coding language.

During her residency, Lilia worked with Niki and her peers to create a multimedia project called “Neglection.” The project depicts the 2020 Belarusian protests and the nation’s larger struggle for freedom. Each scene allows viewers to experience the dictatorial context under which people live in Belarus.

“Neglection” was debuted at the 2022 Oslo Freedom Forum, HRF’s renowned global human rights conference hosted in Oslo, Norway. Exposure to “Neglection” prompted new collaborations with other artists and activists in HRF’s community. For example, Lilia is working with another Belarusian activist to bring attention to the vast number of political prisoners. She is creating portraits of the prisoners, which are to be published on social media and mailed to the prisoners to remind them that they are not alone. This is just one of many collaborations that Lilia has underway.

In addition to her advocacy, Lilia is working toward her Bachelors in Fine Arts at Texas State University. In her spare time, she continues to produce political art, and is now re-learning the history of Belarus. She was shocked to discover that her school in Belarus never explained how Lukashenko held illegal referendums or murdered opposition leaders. Foundational knowledge of Belarus’ history allows Lilia to be more thoughtful, intentional, and audacious in her artwork.

When Lilia first met our team, she didn’t think art could be a full-time career — she just wanted to show her solidarity with the protesters back home. But now, armed with her experiences from the Art in Protest Residency program, Lilia is on the frontlines, using art to confront dictatorship. Her pieces educate the international community about the situation in Belarus and inspire Belarusians to continue advocating for democracy and human rights.

Art is a grave threat to authoritarian regimes because it creatively unmasks their lies. As a result, dissident artists face constant threats and often lack adequate resources. The international community needs to stand up for freedom of expression, protest art, and artists at risk. Click here to help young, at-risk artists like Lilia improve their artistic capabilities, secure meaningful career opportunities, and use their art to influence social change.