The Blurry Lines Between Private and Public

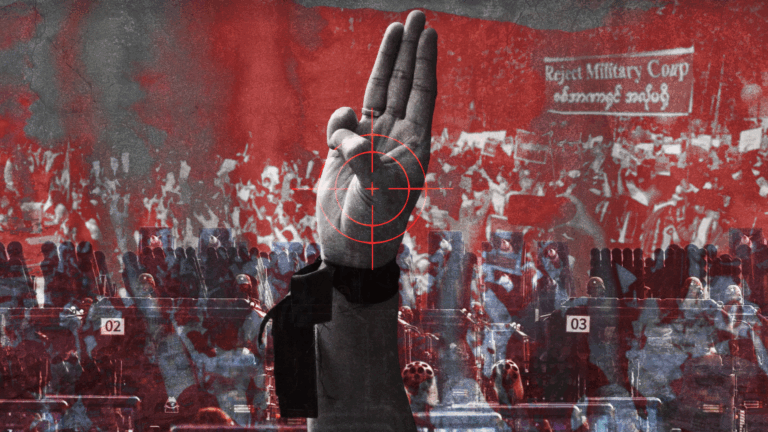

Politics is inescapable for investors, whether they like it or not. This doesn’t mean every company or wealthy individual must feel compelled to publicly endorse causes or candidates. But it does mean that investments — whether in the United States, Chile, or Poland — are inevitably shaped by laws, regulations, taxes, and the broader political climate. It’s never simple, but democracies like these offer elements crucial for doing business: The rule of law, independent institutions, and broad respect for freedom of speech and dissent. These things make it possible for the public to distinguish between the state and private actors, and this separation is a feature, not a flaw, of democratic systems.

In authoritarian regimes, this distinction deconstructs. The tighter a regime’s grip on society, the more meaningless the line between private and state becomes. In some cases, the “private” label is little more than a façade. This is why economic engagement in these environments carries political consequences, even when they are not immediately visible. Circumventing an autocratic regime to invest or do business with nominally private actors can be painfully difficult. Investors should also be wary that the control autocrats exert over the economy is not always obvious, and it no longer resembles the more overt ideological grip seen behind the Iron Curtain in the 20th century that kept foreign capital out entirely.

Cuba’s faux private sector

Although not typically considered an emerging market, Cuba offers an important example of how an authoritarian regime can manipulate the perception of private enterprise. While the country remains a one-party communist state, its leadership has sought to appear reform-minded, seeking foreign investment in select industries and showcasing a budding independent private sector. All of this while the island country suffers from its most devastating economic crisis in recent memory, even dwarfing the 1990s so-called Special Period.

In 2021, months after the largest pro-democracy demonstrations in Cuba in modern history were crushed, the country legalized the creation of small- and medium-sized enterprises (MIPYMES), declaring them independent of state control. On paper, this move was intended to signal a break from the command economy and a willingness to open to the outside world. In practice, the regime maintained overbearing regulations over private economic activity in the country, using the creation of MIPYMES as a lobbying tool to encourage the United States to lift its decades-old trade embargo.

While many still hold the belief that freedom in Cuba can only be obtained by abandoning current sanctions and expanding trade and investment between the US and Cuba, the regime’s signs are far from encouraging.

Investigations by independent outlets like ADN and journalists like Norges Rodríguez reveal that many of the newly licensed “entrepreneurs” are actually members of Cuba’s political and military elite. Ties to the Communist Party, the armed forces, or the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution often determine who receives a license and who is allowed to remain in business. In other words, the so-called private sector isn’t independent at all. The regime wants sanctions to be lifted not to liberalize, but to remain in power.

Even in the more established tourism industry, foreign investment is deeply entangled with the Cuban dictatorship. The Grupo de Administración Empresarial S.A. (GAESA), a military-controlled conglomerate, controls nearly the entire tourism sector and other critical areas of the economy, including remittances, banking, and trade. All capital flowing into Cuba’s key industries must pass through partnerships with a regime-controlled entity. Hospitality giants like the Spanish Meliá and Iberostar — both of which have operated on the island since the 1990s — do collaborate directly with GAESA. While these companies may project neutrality to foreign audiences, helping promote the idea that tourism will boost the local economy and foster cultural exchange, the reality of the Cuban system tells a different story. The local operations of these luxury hotels primarily serve to enrich and empower a small elite within a regime that currently holds nearly 1,000 political prisoners and shows no sign of loosening the totalitarian grip it has maintained on society for more than 60 years.

China: Capitalism with party characteristics

It’s impossible to discuss investment in authoritarian regimes without China, now the world’s largest exporter of manufactured goods and the backbone of global supply chains. Since Deng Xiaoping’s reforms in the 1980s, China has seen rapid economic growth and lifted millions out of extreme poverty. Many hoped economic liberalization and integration into the world economy would steer China toward democracy. Instead, under Xi Jinping, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has recentralized power, tightened repression of dissent and minorities, and taken an increasingly hostile stance toward Taiwan and other democracies — all while courting foreign investors and flooding the world with Chinese goods.

Since Xi’s rise in 2012–13, the CCP has steadily deepened its control over private firms. Originally required by the Company Law of 1993 to form party organizations in firms with three or more members, enforcement was sporadic until a renewed push after 2012. By 2018, roughly 73 percent of private companies had established party organizations — up from around 58 percent in 2013. Among China’s top 500 private firms, more than 92 percent host CCP units, and it became mandatory in 2018 for domestically listed companies. These cells are more than symbolic — they increasingly participate in strategic decisions and personnel vetting and ensure alignment with party policy.

This shift reflects a deliberate strategy: consolidate control over the economy by embedding political oversight at every level. By 2021, more than 40% of small and medium businesses and more than 92% of China’s top 500 firms had Party cells. Even some large foreign companies operating in China have been pushed to incorporate these units.

The CCP’s objective is obvious: no enterprise should operate beyond the party’s reach. This political grip is reinforced by economic pressure. Under the banner of “Common Prosperity,” Xi’s government has demanded massive financial contributions from top private firms, in particular from the tech and finance sectors. Alibaba and Tencent each pledged ¥100 billion (approximately $15.5 billion) by 2025 toward party-aligned initiatives. At the same time, the regime has cracked down on firms seen as too powerful or too independent.

In late 2020, the CCP abruptly halted the Ant Group IPO — then set to be the world’s largest, around $34-37 billion — only days after Chinese businessman Jack Ma criticized financial regulators. It was a clear signal that private success offers no protection from party control. Tech giants like Meituan, Tencent, and Didi have since faced waves of antitrust fines, mandated restructuring, app suspensions, and public admonishment. These moves are not about rule-breaking; they’re designed to reinforce state dominance.

Business success in China today depends more than ever on political loyalty. Firms must showcase alignment with state goals, not only through public messaging but also via their ownership structures, hiring practices, and corporate charters. Foreign investors are not exempt from these dynamics. Operating in China means entering a market where legal protections are conditional, corporate autonomy is constrained, and success increasingly depends on signaling political alignment. Regardless of how detached an investment may appear from the state, whether in tech, manufacturing, or consumer goods, no capital enters China without reinforcing the system that governs it. The CCP’s expanding control over the private sector ensures that foreign money ultimately serves party objectives. Investors must recognize that doing business in China is not just commercially risky; it’s politically entangling. There is no sidestepping the regime.

The costs of complicity

Investors often underestimate the risks of entering these markets. They may assume that because a company is listed on an exchange or has private shareholders, or that a potential partner is publicly registered as an “entrepreneur,” they operate independently. But in fully authoritarian regimes ranging from powerful China to Cuba, that assumption doesn’t hold.

Economic liberalization, when it occurs in the absence of political accountability, does not empower citizens; it strengthens autocrats. Recent history has shown us that when foreign capital flows into these systems, whether through joint ventures, ETF exposure, or direct investment in nominally private firms, it ends up reinforcing the power and control the regime has over its citizens. And in the case of China, it is now helping export the authoritarian norms of the regime to the rest of the world.

In authoritarian countries, the distinction between private enterprise and state power is not just blurry; it is often meaningless. What appears to be a simple market transaction may often end up empowering regime actors. Profitable investments may end up supporting surveillance, censorship, or political imprisonment. Investors, companies, and governments in democratic societies need to recognize this reality and act accordingly.