Read The Signal

How much does North Korea depend on China and Russia for its future? Rachel Minyoung Lee on nuclear weapons, technology transfers, and a newly emboldened Kim Jong Un.

Of all the ways the war in Ukraine could have gone, few people predicted—or even imagined—that soldiers from North Korea would end up fighting in Europe on behalf of Russia. But that’s what happened.

In October 2024, Pyongyang agreed to send 10,000 troops to Russia’s Kursk region to help push back Ukrainian forces from Russian territory. Moscow and Pyongyang tried to hide it—the North Korean troops got Russian uniforms and fake identities—but North Korea’s Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un acknowledged the troop transfer in April this year.

By now, at least 2,000 North Koreans have died in Russia, with some estimates as high as 4,000. In June 2025, Kim announced he was sending Kursk another 1,000 soldiers to clear mines and about 5,000 military construction workers to rebuild infrastructure in the region.

This unprecedented military support is the most striking part of the new, broad alliance between North Korea and Russia. They signed a comprehensive treaty in June 2024, covering political, military, and economic cooperation. Pyongyang started selling arms to the Kremlin in late 2023 and has become Russia’s biggest external supplier, sending millions of artillery shells, rockets, and mortar rounds, along with launchers and missiles.

The new relationship means a lot for North Korea, too. Though some defense deals remain secret, reports indicate North Korea is getting fighter jets, missile systems, technology for reconnaissance satellites, and assistance with nuclear-submarine development and tactical-nuclear capabilities. It’s also getting critical economic commodities, along with a tourist train that began running between Russia’s Vladivostok and North Korea’s Rason in May.

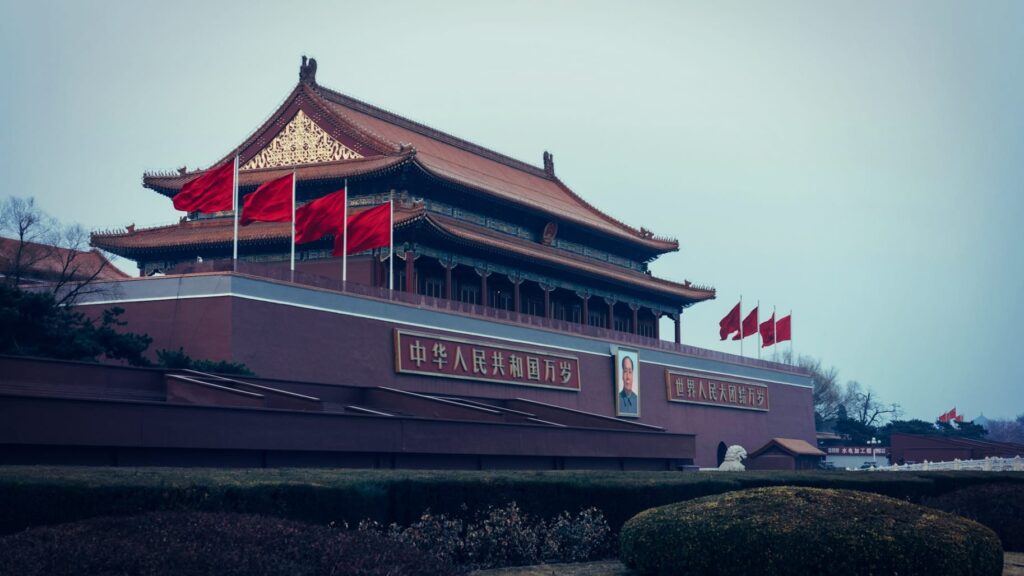

The partnership’s implications seem big: When the Chinese Communist Party held its Victory Day celebrations on September 3 to commemorate the 80th anniversary of Japan’s surrender to China at the end of World War II, Kim and Vladimir Putin got the seats on either side of Xi Jinping.

What’s changed?

Rachel Minyoung Lee is a senior fellow in the Korea Program at the Stimson Center in Washington and a former intelligence analyst for the U.S. government. Lee says the new relationship with the Kremlin has emboldened Kim Jong Un. Maybe most importantly, he’s acting more boldly about his country’s nuclear program. In September 2024, North Korea codified its possession of nuclear weapons into its Constitution, and Kim says he won’t even talk about giving them up. His strong backing in Moscow appears to be influencing how Kim deals with China and South Korea.

It might also be changing how China deals with him: As his seating at the Victory Day parade—and summit with Xi—suggest, Beijing now seems to want stronger ties with Kim to balance his tilt toward Moscow …

Michael Bluhm: What’s the extent of the cooperation between Russia and North Korea now?

Rachel Minyoung Lee: According to open sources, it’s very extensive. It’s been institutionalized, and it’s happening at all levels—from student and cultural exchanges to meetings between top officials.

The two countries are in a kind of a honeymoon phase now. It’s remarkable how regular these high-level summits have become. Their foreign ministers—Choe Son Hui and Sergey Lavrov—have held two strategic dialogues in the past two years.

Kim Jong Un has met repeatedly with Sergei Shoigu, who’s one of Putin’s closest confidants—and has been visiting Pyongyang frequently. They’re likely discussing where they stand on key regional and international issues. In August, Kim had a phone conversation with Vladimir Putin—just days before Putin met with President Donald Trump in Alaska.

They’re being faithful to the treaty they signed in June 2024, which talked about expanding and strengthening cooperation and exchanges between the two countries. Putin and Kim have already started talking about longer-term steps. That could cover a potentially protracted war in Ukraine or after the war.

Bluhm: What’s Pyongyang getting out of this?

Lee: North Korea seems to be reaping economic benefits like shipments of wheat and oil. Kim is probably getting paid for sending troops to Russia.

North Korea is getting political cover from Moscow at the UN Security Council. A primary example: shutting down the UN panel of experts for North Korea. China abstained from the vote to renew the panel in March 2024, but Russia vetoed the extension of its mandate. The panel was disbanded the following month.

I believe Kim thinks about this as a long-term relationship. I don’t think it’s a transactional, short-term thing that comes to an end when the war ends—at least from North Korea’s point of view.

Pyongyang is also getting military technology. There’s plenty of evidence that the Russians have been giving North Korea things beyond what they’ve publicly announced, though we don’t know exactly what the Kremlin has given Pyongyang.

Bluhm: What do you think this relationship will look like after the Ukraine war ends?

Lee: I’m concerned about the potential opportunities in the long term for Kim Jong Un. When I talk to Russia experts, most of them think this relationship pretty much ends when the war does. But I believe Kim thinks about this as a long-term relationship. I don’t think it’s a transactional, short-term thing that comes to an end when the war ends—at least from North Korea’s point of view—for two reasons.

One is Kim’s public rhetoric. In North Korea, his words mean everything. Nothing is more important. And he is 2,000 percent into the war. He publicly justified sending his troops to Russia. He has repeatedly said, If I had to do this again, I would. If there is a future scenario where our troops are needed, then I will send more troops to Russia. He has stated that publicly, repeatedly, and consistently.

The second reason is that Kim’s not just sending weapons—he’s sending human beings. Someone might write that off and say, He’s a dictator. He doesn’t care about his people.

But sending human beings carries a different weight. State propaganda about troops shows it—it’s all about sacrifices and fallen soldiers. Kim has gone out of his way to play up the sacrifices of these troops.

Bluhm: What do you mean by potential long-term opportunities for Kim?

Lee: The 2024 treaty between North Korea and Russia covers cooperation in almost every field you can think of: political, diplomatic, military, trade, investment, cyber, IT, and more. Since then, they’ve taken steps to deepen and expand their relationship across all those fields. And I think Kim wants them to make more progress on increasing their cooperation across these fields while the war continues.

Two major potential repercussions could be the modernization of North Korea’s military and the revitalization of its munitions and defense industries. Russia can help revitalize these industries, and that would have potentially important implications for the North Korean economy.

It would also have repercussions for North Korea-U.S. relations, like future nuclear negotiations, and for inter-Korean relations and possibly North Korea-China relations.

Bluhm: Do you see any effects of this increasing closeness between Moscow and Pyongyang on North Korea’s relationships with South Korea and the U.S.?

Lee: Yes, definitely—this relationship has emboldened Kim Jong Un.

It’s contributed to Kim taking a harder line on his nuclear weapons. We constantly see reports about Kim visiting weapons facilities or overseeing some weapons development. Last September, North Korea codified its nuclear status into its Constitution. And they’re using that as a reason they can’t give up their weapons.

And that has an impact on how North Korea deals with the U.S., and it’s going to continue to have an impact on nuclear negotiations. For example, Kim just said earlier this fall that denuclearization is off the table. If the U.S. administration is willing to drop denuclearization from the negotiating agenda, then Kim might be willing to meet with Trump.

If the U.S. administration is willing to drop denuclearization from the negotiating agenda, then Kim might be willing to meet with Trump.

Kim’s relationship with Russia has also affected his relationship with South Korea, in my view. In December 2023, North Korea announced a huge policy shift on inter-Korean relations. It renounced unification and defined South Korea as a hostile country. Analysts have offered a few possible explanations why.

One is that South Korea is so much wealthier and more militarily powerful in conventional terms, so Kim wanted to make a clean break. Another is that Kim wants to demolish any hopes of reunification—which many North Korean people probably want—because that represents a potential threat to his regime. Another is that Kim wants to exclude Seoul from all future talks with the U.S.—he only wants to deal directly with Washington.

But look at the timing of the policy shift: December 2023 was right when North Korea’s relations with Russia were burgeoning. It’s not long after the summit between Kim and Putin. And it’s right when North Korea’s munitions and defense industries really started taking off. I definitely see a connection here.

Bluhm: What’s the relationship between North Korea and China like now?

Lee: The relationship is on the mend, but it hasn’t been fully restored. We know it wasn’t in a great state for about two years, from fall 2023 until recently. This September, Kim accepted Xi Jinping’s invitation to attend the celebrations in Beijing for the 80th anniversary of China’s victory in World War II. Kim sat next to Xi, and after the celebration, Kim and Xi had their first summit in about six years.

I’ve seen lots of reports in international media saying North Korea and China are getting close. I’d be a little cautious about putting it that way. I’d say they’re working toward getting close.

North Korean media have reported on some high-level summits and two letters from Kim to Xi, and those reports do not exude warmth. That tells me Kim didn’t exactly get what he wanted from Xi at their September summit. The language of North Korea’s summit readout didn’t say the two leaders reached consensus on anything. There wasn’t any mention of alignment or even that Kim felt satisfaction. The wording was very cool—it said they “notified each other of their positions.” Compare that to 2018 and 2019, when Kim and Xi met five times.

That said, China needs North Korea, and North Korea needs China, so I think they’ll make the effort to repair things.

In the bigger picture, North Korea sees China and Russia playing different roles. Russia will do things that China won’t do, like outright violating sanctions for North Korea. Putin himself said he was against unilateral sanctions against North Korea, whereas China is more careful because it has bigger stakes all around the world. It still cares about being viewed as a responsible member of the international community. China won’t buy weapons from or send military technology to North Korea.

The flip side is that Russia just doesn’t have the economic resources that China does to help the North Koreans. China usually accounts for more than 95 percent of North Korea’s total trade volume every year. Russia could never do that. Russia is not replacing China—it’s complementing China, and vice versa.

Bluhm: Do you think Kim’s increasing closeness to Russia is influencing the trajectory of his relationship with China?

Lee: Yes. It’s affected North Korea’s policy on China, because it’s given Kim more options.

Would North Korea’s relationship with China have cooled off so much if Russia hadn’t been there for Kim? And even if it had cooled, would that have lasted two years without Russia?

We’ll probably never know what caused the friction between North Korea and China from fall 2023 until now. I can only speculate that Kim wanted something from China, but the Chinese didn’t give it to him, so he was upset.

Would North Korea’s relationship with China have cooled off so much if Russia hadn’t been there for Kim? And even if it had cooled, would that have lasted two years without Russia? I think those are questions worth asking.

I believe that Kim having more options—and having what Russia gives him—did have an effect on how North Korea interacted with China.

Bluhm: Kim’s father and grandfather used to try to play Moscow and Beijing off each other, to get as much as they could from each one. Do you think Kim’s continuing that tradition at all today?

Lee: It’s hard to say, because it’s a completely different environment today—though maybe you could argue that the essence of great-power politics hasn’t changed that much.

But I don’t think Kim Jong Un even has to play them off each other. For instance, I think China was more desperate to get the North Koreans to Beijing for the World War II celebration than the other way around, because it appears that Beijing was getting anxious about how close the North Koreans and the Russians were getting. The problem for China is that if and when North Korea and the U.S. start to engage, the Chinese don’t want to be left out.

If Kim and Trump were to meet—and that might happen next year—then Xi Jinping would want to be the one who meets with Kim before and after the summit. That’s exactly what happened in 2018, before and after Kim’s first summit with Trump. But with the way things have gone between Kim and Xi the last two years, the Chinese were afraid that wouldn’t happen again—and that, instead, the North Koreans would be going to the Russians for consultations.

So in this instance, Kim didn’t even have to play them off each other. The Chinese are increasing their bidding on their own.

Bluhm: Lucan Way says he doesn’t think this alliance of autocracies—China, Russia, and North Korea—represents a serious threat to the West, mainly because they don’t trust each other and don’t share much other than opposition to U.S. power. What do you make of that?

Lee: I agree. It’s a catchy idea—an axis of autocracies. And these three countries do share the broader goal of working against a global order led by the U.S. and the West. But their individual goals are different.

More importantly, North Korea, China, and Russia are not an “axis.” Maybe it depends on how you define that, but they aren’t that kind of coalition. They don’t have that level of unity. Look at what happened in Beijing at the massive World War II commemoration: There wasn’t a three-way North Korea-Russia-China summit. There was a Kim-Xi summit and a Kim-Putin summit.

Which is so representative of what’s happening right now. You have three sets of bilateral relationships, or you could say three sets of dyads. But there’s no trilateral coalition.

Even if the Russians and North Koreans wanted to create one, I think China would be very reluctant. They wouldn’t want to be tied to the Russians and North Koreans that way.