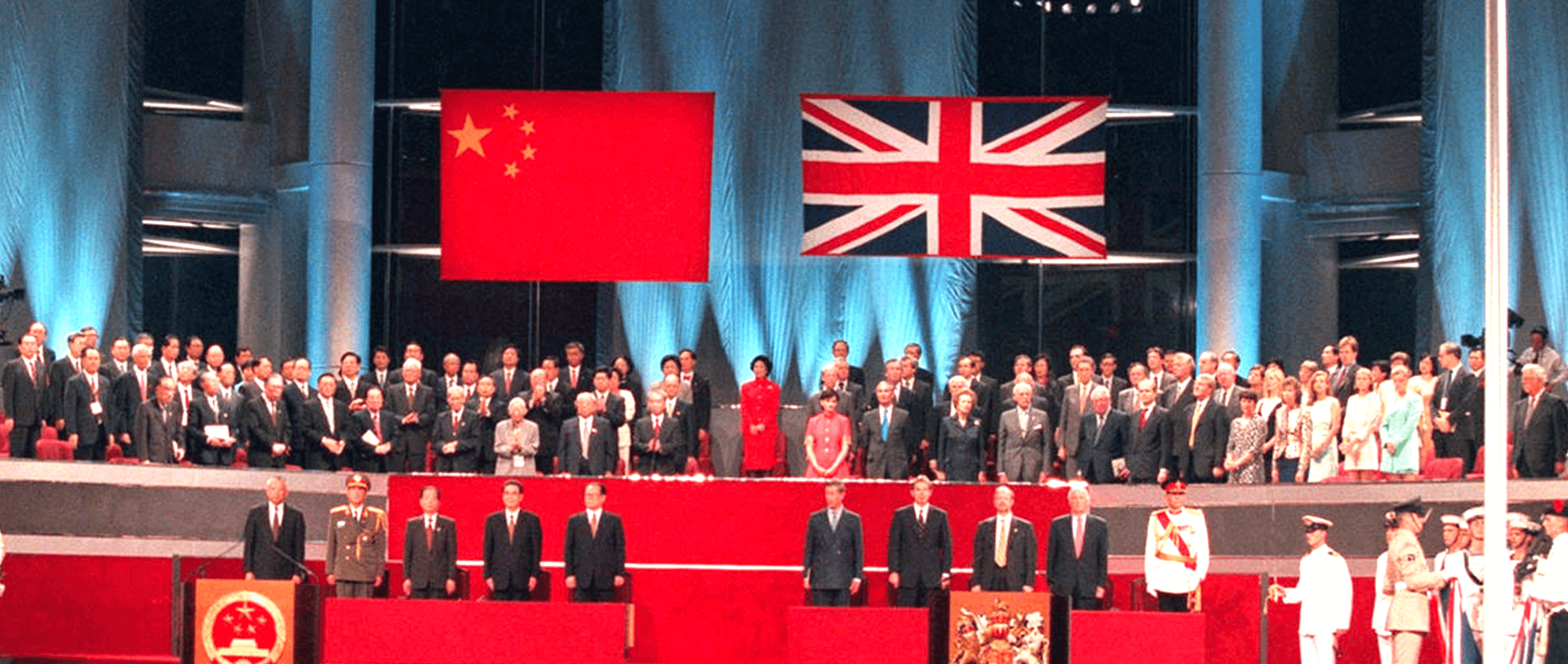

On July 1, 1997, the former British colony, Hong Kong, was handed back to the Chinese government after a 99-year lease between China and Britain expired. Since then, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region has been governed under the “One Country, Two Systems” model. As the draconian Hong Kong national security law goes into effect this week, this optimistic model of governance has come to an end almost exactly 23 years after it began.

Over the past year, Hong Kong, a major Asian financial hub and bastion of free expression and enterprise, has been rocked by street protests and police crackdowns on civil society. On June 9, 2019, millions marched to oppose extradition legislation that would transfer Hong Kong citizens to be tried in China, where rule of law is severely lacking.

The protests persisted even after the legislation was suspended. As the COVID-19 pandemic raged, Hongkongers remained furious about ongoing police brutality and arbitrary arrests.

Responding to the Hong Kong government’s failure to quiet the protests, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) took things into its own hands by announcing that it would circumvent the legislative process in Hong Kong to directly promulgate the national security law, which imposes heavy imprisonment on vaguely-defined charges. Yesterday, the draconian law was officially signed into effect, threatening pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong with life imprisonment. The atmosphere is now grim in Hong Kong, triggering many locals to discuss fleeing the city and emigrating elsewhere, forcing many to shutter their social media accounts out of fear of reprisal, and bringing about the disintegration of pro-democracy organizations.

But how did Hong Kong get here?

Introduction

For more than a century, Hong Kong enjoyed individual freedoms under British rule. People in Hong Kong were afforded liberties such as those guaranteed under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, including freedom of religion, freedom of peaceful assembly, and freedom of expression.

Under the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984, an international treaty that laid out the terms of the handover, the authoritarian Chinese government promised that Hong Kong would be designated a special administrative region under the “One Country, Two Systems” model, and would be able to enjoy its democratic freedoms and civil liberties for a transitional period of fifty years, until 2047. The British government handed Hong Kong back on these terms, expecting that with the opening of China’s trade, the government would democratize and Hong Kong’s liberties would be preserved.

Unfortunately, that optimistic prediction has not been realized. Instead, the international community has witnessed how the Chinese government has continuously tightened its authoritarian grip in both mainland China and Hong Kong.

Political System

According to the Human Rights Foundation’s political regime analysis, China is ruled by a fully authoritarian regime in which there is a lack of respect for the fundamental rights of citizens, and there is no separation of powers or judicial independence.

The “one country, two systems” principle outlined a unique governing structure in which Hong Kong’s government would enjoy a high degree of autonomy.

Hong Kong has its own mini-constitution, executive government, legislative council, and judiciary, which are all designed to function separately from the mainland Chinese political system. However, in practice, the executive government of Hong Kong is merely a puppet of the CCP, as the highest position in the government, the chief executive, is elected by a small group of predominantly Beijing loyalists and approved by the CCP, rather than through free and fair elections.

The Hong Kong Legislative Council (LegCo), while allowing for a multi-party system that includes pro-democracy legislators, is mostly pro-Beijing. Pro-democracy candidates face obstacles in running in the LegCo elections, such as disqualification based on frivolous conditions, vote-rigging, and voter suppression. Overall, pro-Beijing legislators have primary control of LegCo, and set Hong Kong’s political agenda to please the CCP.

The Hong Kong judiciary, built on the British judicial model, is historically independent and impartial and often a source of pride for Hongkongers. However, since the 2014 Umbrella Movement, there has been increased prosecution of pro-democracy activists. The persecution of activists was exacerbated during the 2019 protests with the prosecution of numerous protesters, many of whom were peaceful, under rioting charges that carry imprisonment up to 10 years.

The original vision of “One Country, Two Systems” has been under threat ever since the 1997 handover. Under pressure from the CCP to assimilate the westernized Hong Kong into China, the Hong Kong government has increasingly been incorporating authoritarian tactics into the governance of Hong Kong.

The Erosion of “One Country, Two Systems”

The erosion of “One Country, Two Systems” has been gradual over the past 23 years. In the past, the CCP primarily acted through its pro-Beijing government officials within Hong Kong’s executive branch to advance its political agenda, such as enacting laws to curb the freedoms that Hong Kong had enjoyed in the past under British rule.

The first prominent case of the Chinese government overstepping Hong Kong’s autonomy was the Causeway Bay Books incident in late 2015, when five staff members suddenly went missing. Causeway Bay Books was a small popular bookstore that sold banned books about the CCP. One of the owners of the bookstore was kidnapped from Hong Kong and reappeared in mainland China, raising concerns that the Chinese security bureau, which does not have jurisdiction in Hong Kong, had violated Hong Kong’s autonomy by kidnapping the bookstore owner across the border.

The Causeway Bay Books incident demonstrates how Hong Kong’s press freedom has been in rapid decline as it is confronted with immense pressure from the Chinese government. Few independent media outlets remain in Hong Kong. Freedom of association has also been under threat in Hong Kong, with the government rejecting registration of pro-democracy groups.

A salient example of the Hong Kong government’s strong rejection of pro-democracy groups was when four democratically-elected LegCo officials were disqualified from their positions in 2017. The four pro-democracy lawmakers had all been involved in the 2014 Umbrella Movement just a few years ago. One of these lawmakers was Nathan Law, the founding chairman of the now-shuttered youth democracy activist group, Demosistō. Law was the youngest elected official in Hong Kong’s history. The disqualification of these four individuals further fueled fears of how Beijing was increasing its influence within Hong Kong’s internal affairs.

In 2019, the Hong Kong government proposed an extradition law, the Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation (Amendment) Bill 2019, which would allow the Hong Kong chief executive to extradite fugitives on a case-by-case basis, bypassing legal procedure. While the bill does not specifically target extradition to mainland China, extradition of Chinese fugitives would be especially concerning because of the lack of judicial independence and rule of law in China. The proposal of this bill led to an outpouring of concern amongst Hong Kong citizens, and citizens of other countries passing through Hong Kong, that they may be extradited to China on politically-motivated charges. The general public in Hong Kong saw the bill as Beijing’s latest attempt to attack the fundamental freedoms in Hong Kong, and millions of people joined protests in the streets to demonstrate against the passage of the bill.

The 2019 protests surrounding the extradition law gathered widespread international support but also alarmed the CCP that Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement is strengthening and threatens the CCP’s control over the city. To stamp out pro-democracy voices in Hong Kong, the CCP grew impatient waiting for pro-Beijing legislators to act on its behalf and announced in Spring 2020 that it would instead circumvent the established legislation procedure in Hong Kong to directly impose a national security law on the city. According to Hong Kong’s mini-constitution, the Hong Kong Basic Law, the CCP does not have direct power to promulgate a national security law for the city, and instead the law should be enacted by LegCo only. However, at the National People’s Congress (NPC) in June, China’s annual party member gathering to rubber-stamp policies, the CCP announced that it would directly enact the national security law and avoid Hong Kong’s own legislative procedure. The passage was conducted behind closed doors, with no transparency to the legislative process. In fact, the Hong Kong chief executive herself confessed to not having read the text of the law before it was passed.

The national security law criminalizes vaguely-defined actions such as sedition and subversion, which can be used broadly to imprison activists and opposition politicians. It imposes heavy sentencing as severe as life imprisonment, and outrageously extends jurisdiction to anyone who is not a Hong Kong citizen, or commits the criminalized acts outside of Hong Kong territory. The law also calls for the creation of the infamously opaque Chinese security bureau in Hong Kong. In mainland China, the security bureau agents are often responsible for disappearing dissidents and imprisoning them arbitrarily without legal representation and trial. Additionally, the law gives special jurisdiction to the mainland courts to hear certain cases, putting activists at risk of becoming victims of China’s unfair judicial process. The mainland Chinese judicial system is highly politicized, and court hearings are not conducted impartially; defendants often are refused legal representation, and cases are often heard in closed hearings where defendants do not have the opportunity to present their arguments.

The promulgation of the national security law is largely seen as the nail in the coffin for “One Country, Two Systems,” as the law allows for cross-border law enforcement between mainland China and Hong Kong. Many fear that leading pro-democracy activists, including Joshua Wong, Nathan Law, Agnes Chow, Martin Lee, Jimmy Lai, Margaret Ng, and others would be imprisoned shortly after the implementation of the law.

Case Studies

In recent years, prominent and well-respected figures in Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement have been subject to politically-motivated arrests. These actions point toward how Beijing is exerting stronger pressure on the Hong Kong government to control local activism, stripping the city of its autonomy and encroaching on the freedoms of the Hong Kong people.

The Umbrella Nine

A small group of pro-democracy activists involved in the 2014 Umbrella Movement, a protest movement to demand universal suffrage to elect the chief executive position of Hong Kong, was charged with “incitement to commit public nuisance” for their involvement in the peaceful demonstrations. The group’s individuals, collectively referred to as the Umbrella Nine, were perceived to be leaders and key organizers of the non-violent protests and as a result, were handed prison sentences in April 2019 by the Hong Kong government.

The Umbrella Nine included respected activists such as retired pastor Reverend Chu Yiu-ming, esteemed scholar Benny Tai, and several former members of LegCo. While the government smeared these individuals as troublemakers, in reality, these nine people were solely peacefully exercising their rights to assembly and freedom of expression. The charges against the Umbrella Nine were among the first emblematic examples in recent Hong Kong history showcasing the restriction of civil liberties and foreshadowing the end of the city’s genuine autonomy.

Read HRF’s submission to the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention on behalf of four of the Umbrella Nine here.

Johnson Yeung

Johnson Yeung is an active participant in civil rights campaigns and the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong, and a 2019 Freedom Fellow of HRF. He participated in the 2014 Umbrella Movement, a 79-day protest that paralyzed Hong Kong’s financial center, as well as the 2019 Anti-Extradition Bill protests.

During the 2019 protests, Yeung was arrested for trying to diffuse a dispute between a police officer and a social worker. Police officers recognized Yeung as a well-known activist, and beat, arbitrarily arrested, and subjected him to cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment while in detention. He was later released on bail pending an investigation. Since his release, no formal charges have been filed against him to this day. Johnson Yeung’s case is one of many examples where the Hong Kong government has targeted pro-democracy activists in their arbitrary arrests.

Read HRF’s submission to the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention on behalf of Johnson Yeung here.

The Fifteen Pro-Democracy Leaders

As the world was distracted by the COVID-19 pandemic, Beijing continued to tighten its grip on the Hong Kong government. On April 18, 2020, the Hong Kong police conducted a series of high-profile arrests of 15 prominent pro-democracy activists and politicians, including barrister and former LegCo member Margaret Ng, Hong Kong media tycoon Jimmy Lai, and Hong Kong’s “Father of Democracy” Martin Lee. All of the arrested individuals were accused of organizing the 2019 Anti-Extradition protests, despite the reality that the movement was a decentralized effort of millions of citizens.

These arrests were not surprising: Against the backdrop of COVID-19, and in the days and months leading up to April 18, Beijing had been consolidating its power over Hong Kong’s internal affairs, not only by replacing and appointing new pro-Beijing officials in leadership positions, but also by having the China Liaison Office explicitly declare that it was no longer bound by the “one country, two systems” principle — ultimately allowing Chinese government interference in local affairs, as exemplified in the national security law enactment. The arrests of these 15 individuals who were well-respected among Hong Kong citizens was a clear sign of how Beijing was ready and willing to instill fear among the city’s population.

Read HRF’s policy note on the arrest of the 15 pro-democracy leaders here.

Conclusion

For more than two decades, Hongkongers have fought to keep the city’s democratic values and freedoms. However, under Xi Jinping’s authoritarian leadership, they find themselves facing an uphill battle despite popular international support. With the enactment of the new national security law, Hongkongers expect to see increased persecution of pro-democracy activism.

As accountability and rule of law are nonexistent in China and increasingly difficult to achieve in Hong Kong, Hongkongers should look to the international community to continue advocating for their cause. Cases of human rights abuses should be brought to the United Nations Human Rights Council, as well as addressed in global media.

To curb the spread of China’s authoritarianism in not just Hong Kong, but globally, as Hong Kong has long been regarded as a gateway from Asia to the world, governments internationally should take a clear stance to support Hong Kong’s fight for freedom. There should be government sanctions on Chinese and Hong Kong government officials who are complicit in human rights abuses, whether through the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act or the Global Magnitsky Act. Meanwhile, governments should also consider extending special immigration statuses to Hongkongers who are fleeing from persecution. Companies, non-profits, and sporting leagues conducting business in China and Hong Kong should think twice about their role in China’s subjugation of Hong Kong and should provide information about the effects of the National Security Law to their employees so that no one can claim ignorance about corporate complicity in human rights abuses.

On this 23rd anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover to China, we should recognize the brave activists and dissidents in Hong Kong fighting against authoritarianism from China, and take a stand with them to call for the respect of Hong Kong’s autonomy. The national security law must be repealed, and the Hong Kong and Chinese government must refrain from using it to imprison pro-democracy activists in the city.

You can take a stand with Hongkongers by supporting HRF’s efforts in advocating on behalf of Hongkongers on the international stage. Support HRF’s Hong Kong Desk here.