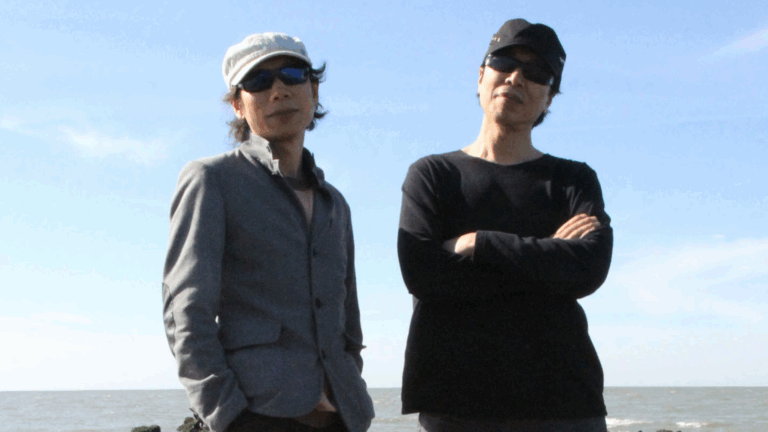

Journalism in Cuba, a totalitarian dictatorship, is an act of defiance. And Abraham Jiménez Enoa, a founder of the Cuban online magazine El Estornudo and a Washington Post columnist, is a strong symbol of that defiance. A prolific writer, Jiménez is part of Cuba’s generation who embraced the few online spaces the regime allowed for civil society when the Internet finally came to the island in the mid-2010s. For years, he faced constant harassment and was barred from leaving the country for telling stories of daily life in Cuba — not just of the decades-long repression against all dissent but of the horrid living conditions of millions of Cubans. The regime goes to great lengths to censor stories such as these; they would dismantle the narrative of an idyllic society they have sold to the outside world for decades.

Shortly after the historic July 11, 2021 anti-regime protests, during which thousands of Cubans took to the streets to demand freedom, the dictatorship launched a massive repression campaign, going after anyone who participated in the protests and the few independent journalists on the ground who covered them. Jiménez was one of them. This time the threats came in the form of an ultimatum: We will allow you to leave the country, but you can never return; refuse, and we’ll throw you in prison for years. He was forced to exile in Spain.

Jiménez’s story is one of hundreds of artists, activists, journalists, and other dissidents in Cuba. Years of kidnappings, character assassinations on state TV, and daily threats of violence to them and their families have culminated in the impossible choice of prison or exile. Those who remain in Cuba are either forced into silence or continue to endure the relentless persecution of a vindictive regime. Camila Acosta, a correspondent for CubaNet and the Spanish newspaper ABC, was kidnapped by regime security forces just this month. Although she was released days later — a common practice of the dictatorship — the regime played a private phone conversation of her with a Miami-based news outlet on state TV, using it to falsely and outrageously accuse her of aiding “neo-terrorists.” Lázaro Yuri Valle Roca, a journalist who also covered the protests in 2021, is languishing in prison after being sentenced to five years for the Orwellian crime of spreading anti-government “propaganda.”

In Nicaragua, the brutal regime of Daniel Ortega, a staunch ally of Cuba’s Communist dictatorship, employs similar tactics to squash the remaining vestiges of independent journalism. After ramping up repression following the massacre of nearly 300 anti-government protesters in 2018, Ortega shut down all independent media outlets through intimidation, police raids, violence, and imprisonment of journalists. According to NGOs Voces del Sur and Fundación por la Libertad de Expresión y Democracia, there are 208 documented cases of Nicaraguan journalists forced into exile. Some of them, like sports journalist Miguel Mendoza, spent nearly 600 days in inhumane conditions in the infamous Chipote prison simply for criticizing Ortega. He was released earlier this year along with 221 political prisoners, but they were all promptly forced into exile and stripped of their citizenship.

The ire of the regime did not only stop at those it had captive but also extended it to hundreds of others it had forced into exile in previous months and years. Carlos Chamorro, one of Nicaragua’s most prominent journalists and the director of the newspaper Confidencial, was among hundreds of other journalists and dissidents in exile who were also stripped of their Nicaraguan citizenship. Chamorro fled the country in 2021 as it became impossible to operate within Nicaragua. In a 2021 interview, he aptly described the situation in Nicaragua as one in a “state of terror,” where nobody dares to go on record to criticize the regime. The conditions for journalists remain dire, as evidenced by the recent arrest and sham trial of Victor Ticay, a TV correspondent who could face up to 10 years in prison for offending the “national integrity” after he recorded a celebration of Easter in the small town of Nandaime. Ortega has banned public Catholic celebrations and imprisoned several church figures, including the Bishop of Matagalpa, Monsignor Rolando Álvarez.

In Venezuela, the third fully authoritarian regime in the region, journalists also face steep challenges as the Maduro dictatorship continues to close down the last independent spaces of traditional media. Last year, the regime arbitrarily closed 79 radio stations, refusing to renew operating licenses in extremely opaque administrative processes. In Bolivia, where the hybrid-authoritarian regime of Luis Arce has ramped up its persecution of the opposition, one of the largest and most prominent newspapers in the country, Página Siete, was forced to shut down in June. The Arce regime deliberately put the newspaper under unbearable financial strain, punishing its editorial line by cutting off government advertising revenue and pressuring private companies to drop the paper.

Even in countries still classified as democracies, where threats to journalists primarily come from non-state actors, we are witnessing an increasingly hostile state stance against independent journalists. In El Salvador, for example, where the administration of Nayib Bukele has seriously eroded democratic institutions, journalists critical of the government have been targeted by the cyberespionage tool Pegasus. The Bukele administration has also replicated Bolivia’s intimidation tactics against advertisers and constantly slanders critical media on state TV and social media. This pressure has already forced El Faro, the oldest and one of the largest online newspapers in the region, to relocate to Costa Rica.

The region as a whole has experienced a sustained and troubling democratic decline, all while authoritarian regimes have ramped up their repression and further solidified their grip on power. This escalating crisis, marked by the silencing of journalists through harassment, imprisonment, and forced exile, is not only an assault on press freedom but also a significant impediment to democratic progress. As we witness the courage of these journalists who risk their lives to tell the truth, we must amplify their stories and advocate for press freedom in Latin America. The resilience of democracy in the region hinges on the ability of the press to operate without fear.